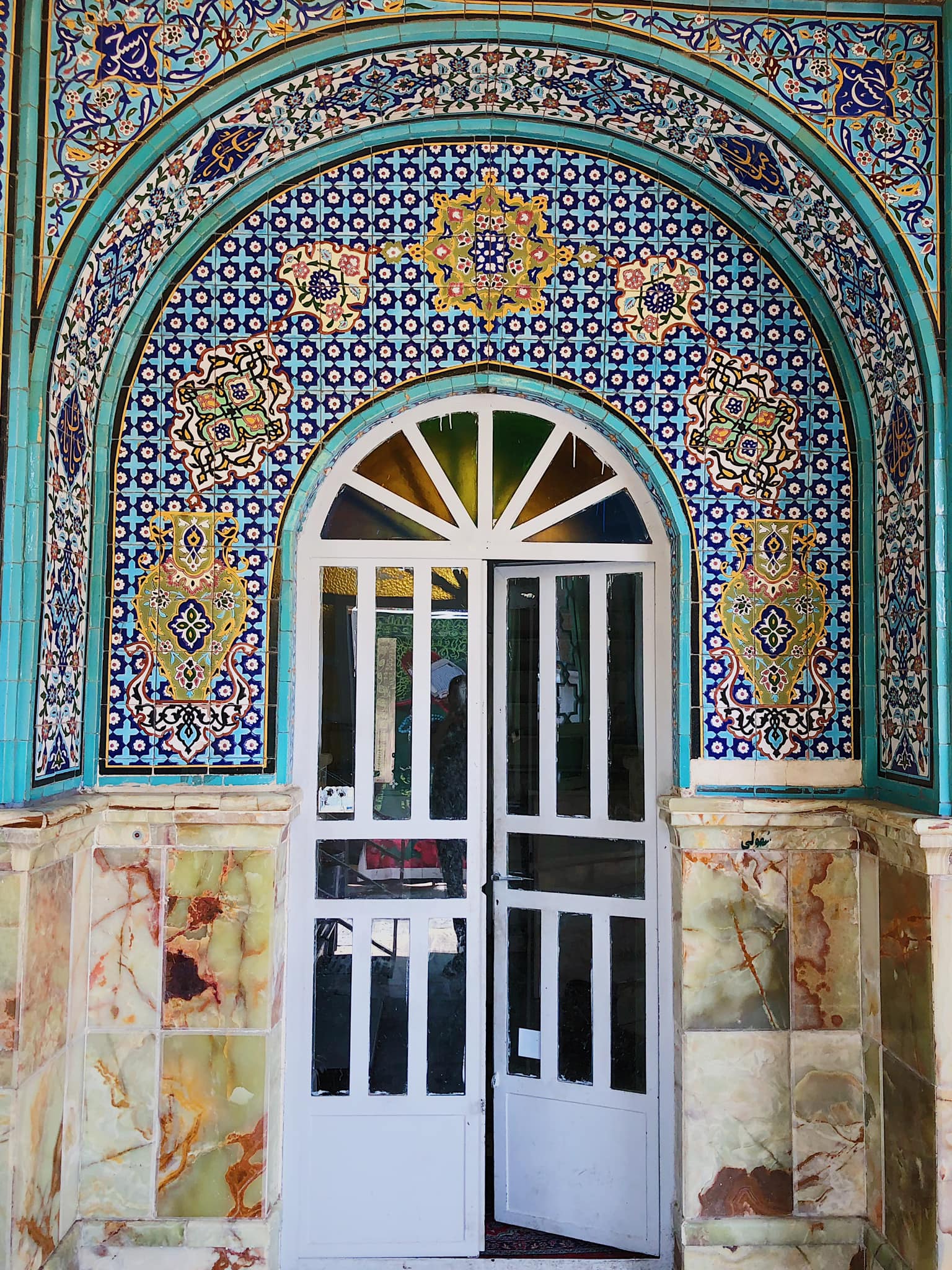

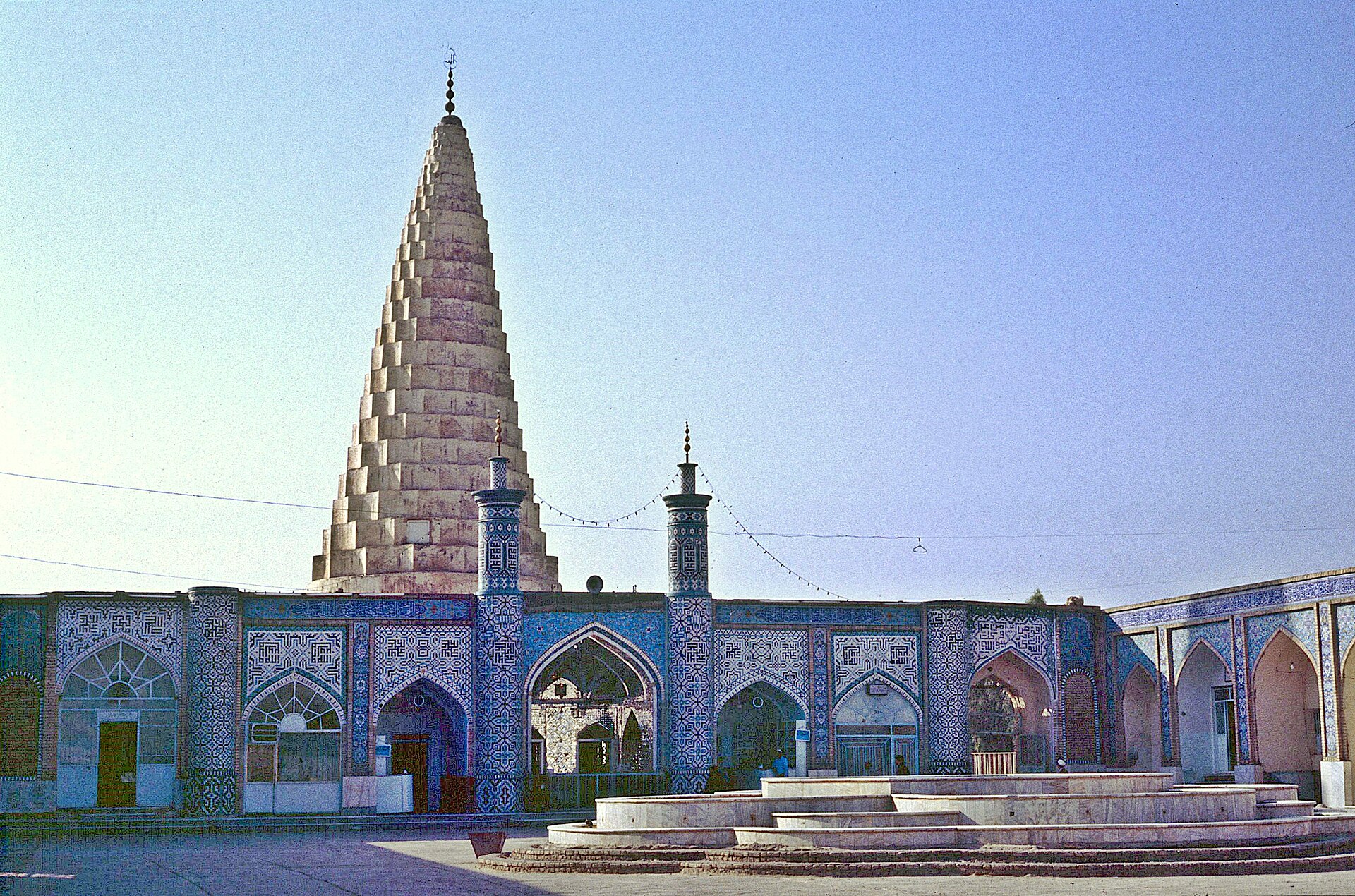

In Qazvin, a few hours west of Tehran, there is a turquoise-blue shrine locals know as Peyghambarieh, “the place of the Prophets.”

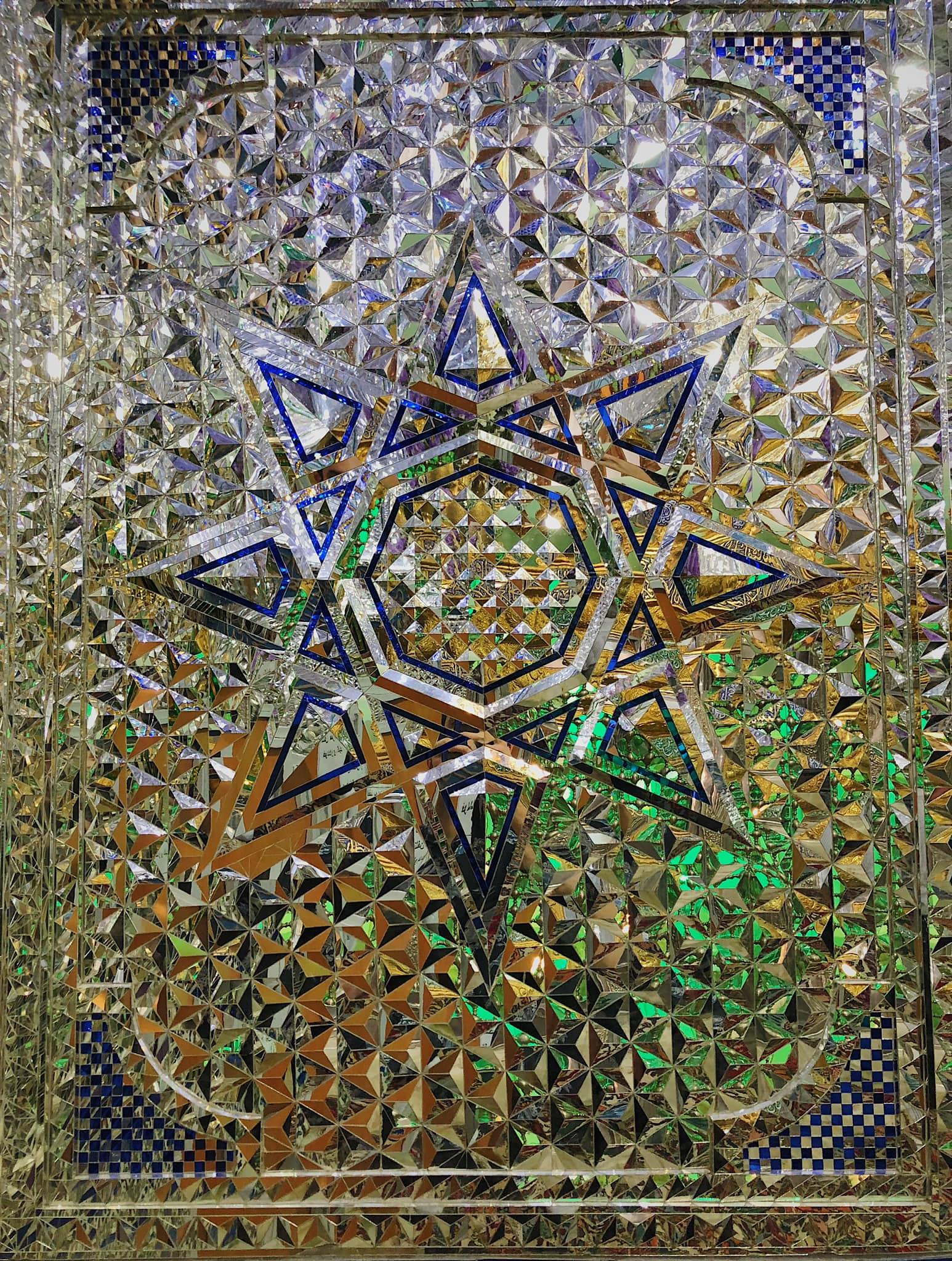

Its walls feature sparkling stars that glimmer across the shrine’s heart and thousands of glistening mirrors reflect green and purple light in every direction. Above the tomb, the names of four holy figures buried there are listed: Salam, Salloum, Sahouli, and Elqia.

Peyghambarieh hosts a constant stream of Muslim visitors for whom the shrine is the resting place of four Jewish holy men who brought news of Jesus Christ’s birth in Bethlehem to Iran, which was then predominantly Zoroastrian. Four religions – Judaism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Islam – come together in a shrine that defies contemporary borders between faiths.

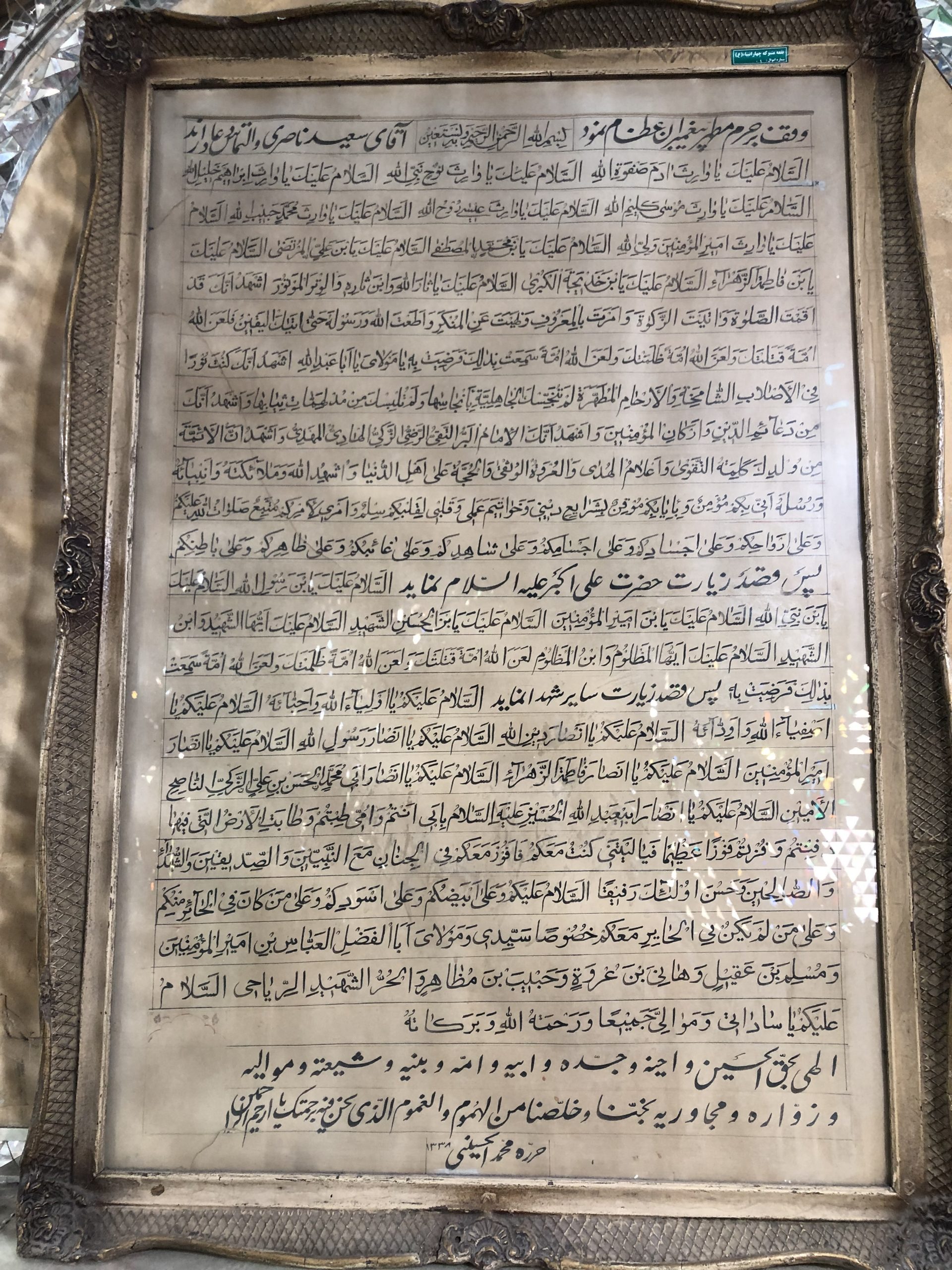

But the site’s history remains a mystery, with few documents or archives pointing to its origin. The prophets’ names are said to derive from a (lost) Hebrew text found in the 1500s. The legend goes that they were Jews from Palestine persecuted by their co-religionists for embracing Jesus Christ as a holy prophet. They came to Iran, bringing word of the Christmas miracle to a mostly-Zoroastrian land with large Jewish communities.

Besides the story that locals tell, however, there is little evidence of the holy place’s origins. Some speculate that Peyghambarieh may actually be the tomb of the Three Magi, the “wise men” who visited Jesus in Bethlehem.

The Three Magi came from “the East” and are thought to have been Zoroastrian priests from Iran. Magi is the plural of Magos, a Greek version of the Persian word “Mogh” or “Majus,” meaning a Zoroastrian priest. The Three Magi supposedly followed a star to find Jesus’ birthplace in Palestine; Zoroastrian priests were famous for their attention to astronomy.

Some say the legend of the Magi developed later among Zoroastrian converts to Christianity, integrating their own holy lore into the new faith. Others argue that it was a Zoroastrian legend that was Christianized over time, like how Christmas is celebrated in late December – a time period that doesn’t quite match the Biblical story, but links up directly with the winter solstice widely celebrated in the ancient world (and in Iran, under the name “Yalda,” یلدا meaning “Birth” ܝܠܕܐ in Syriac).

Marco Polo said he was shown the Three Magi’s tombs in Saveh, not far from Tehran, when he visited in the 1270s.

But Zoroastrians are not traditionally buried, so either he was misled or the Magi had adopted Jewish burial traditions on their return, possibly in recognition of Jesus’ Jewish lineage. But there is no record of such a tomb existing in Saveh, so perhaps Marco Polo mistakenly wrote down Saveh when he meant Qazvin – a strong possibility, given that he wrote his diaries years after finishing his travels.

The earliest documentation we have of Peyghambarieh is from the 1500s, when Qazvin was the capital of the Safavid empire. Most of the city’s historic landmarks date from that time. The women of the Safavid royal court purportedly visited the shrine at the beginning of each lunar month, calling it “Imamzadeh Goroshmaq,” امامزاده گُرُشماق meaning “the shrine of seeing and being seen” in Azeri Turkish, the language commonly used by Safavid royals.

Today, Peyghambarieh is visited in particular by local women, and many give nazri (food or drink distributed freely in honor of the saint) to women at the shrine, suggesting the site’s origins in women’s practices remain strong.

It seems likely that Peyghambarieh was originally located in a Jewish cemetery south of the royal city. The Safavids invited Jewish and Christian communities to settle in their imperial capitals, and Qazvin developed a significant Jewish population. But as Qazvin lost its imperial status, much of the community moved away: to Mashhad in the 18th century and Tehran in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Few sources about the community exist today, so it remains unclear if Peyghambarieh was originally a Jewish place of pilgrimage adopted and eventually taken over by Muslims (similar to Ezekiel’s Tomb), or if from the beginning it was a Muslim site of pilgrimage.

Given that the Jewish holy men buried there are said to have been followers of Christ – a prophet in Islam, but one rejected in Judaism – it could be either.

The story is further complicated when we consider that there is no evidence local Jews saw the shrine as connected to Jesus’ birth. One scholar has argued that the tomb may be home to three of the Prophet Daniel’s companions. Daniel was buried in Shush, in Iran’s Khuzestan province, and today his shrine remains a popular pilgrimage site for both Muslims and Jews.

But the names of his three companions – Hanania, Ezriya, and Michael – don’t fit the names used at Payghambarieh today. Though given that the current names (Salam, Salloum, Sahouli, and Elqia) are derived from a lost manuscript, nothing can be ruled out.

Besides the four Jewish holy men buried there, Peyghambarieh is also home to an imamzadeh, the tomb of a Muslim saint, said to be a descendant of Imam Hassan. This would suggest he was originally buried in the Jewish cemetery. This could make sense given that Islam was understood as emerging from the Abrahamic tradition of Judaism, a connection that would have been particularly strong in an environment like Iran, where most people followed the non-Abrahamic religion of Zoroastrianism.

This is a common pattern in Iranian shrines, where holy figures were often buried in the proximity of existing holy sites. Over time new figures eclipse old figures in importance, especially as the religious affiliation of Iranians around them changed.

One of the intriguing aspects of Peyghambarieh is that it was built and expanded by the Safavids – a Shia Muslim empire – as one of their capital’s main shrines, with the focus primarily on the Jewish figures buried there, rather than the Muslim saint beside them. This could have been a way to integrate the faith of Iranian Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians into the umbrella of Muslim idiom by creating a shared space of worship that integrated elements of each religious tradition.

So is Peyghambarieh the resting place of Jewish prophets or of Zoroastrian Magi?

We may never know the answer. As with all history, this is an attempt at interpretation; our understanding is determined by a mixture of stories and artifacts, narratives and traces. We’re so used to seeking out certainty, but who knows what could be found tomorrow that changes our understanding of it all.

Because shrines survive and attract pilgrims even as empires rise and fall around them and religions come and go, their stories accumulate layers of interpretation and belief over time. These stories offer insight into past worlds that have been buried with the passage of time, and discovery of new evidence can upend what we thought we knew. Recently, archaeologists discovered tombs and tunnels below Peyghambarieh. They may hold secrets that could shed light on the shrine’s history. Or maybe not.

For locals who come to pray and reflect, the identity of the saints is probably less important than the air of holiness that pervades the site and the fact that when they come seeking help for their problems at Peyghambarieh, they continue to find answers.

Regardless, the tale told today in Qazvin has created its own tradition, connecting Iran and Palestine through an ancient connection: the story of Christmas.