Guest writer Felix de Rosen last year traveled from Armenia to Afghanistan, passing through Iran and Tajikistan en route. This article is the third part in a series about his travels (first part in the Caspian foothills of Iran can be found here and second part in Western Afghanistan here).

The village of Sarhad feels like the edge of the world. Here, the land rises into the sky and it’s hard to tell in which I am standing. Looking south, the snowy peaks of Pakistan stand like a silent wall in the distance. To my north and east, the steep inclines of the Afghan Pamirs angle my gaze high into the sky. Facing west, I can see the broad valley floor of the Wakhan Corridor.

Looking West.

Looking West.

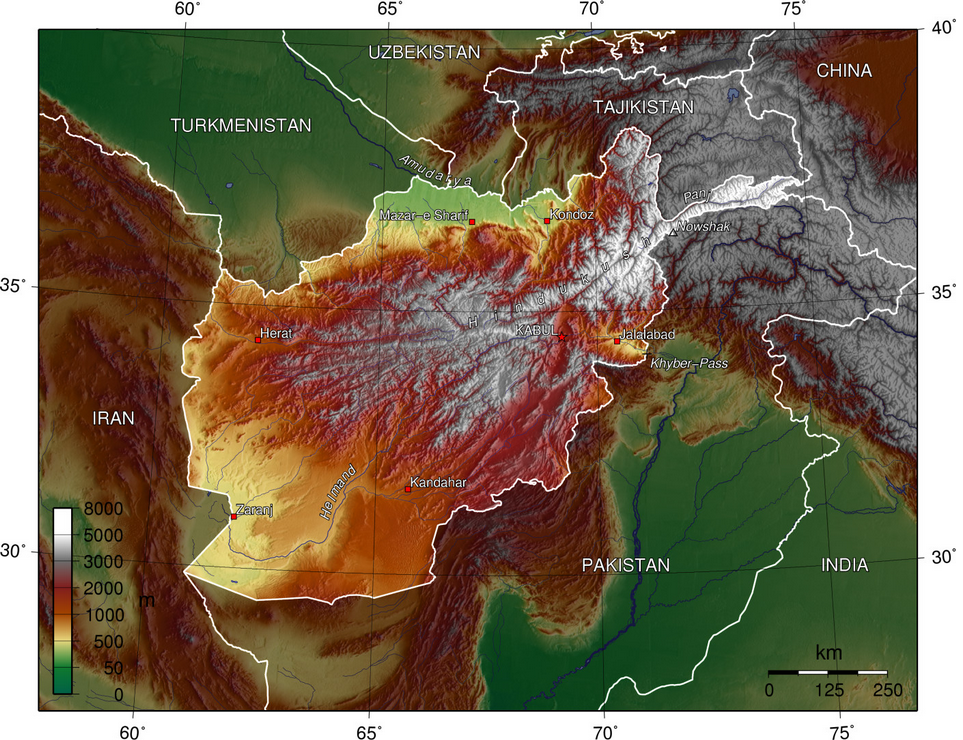

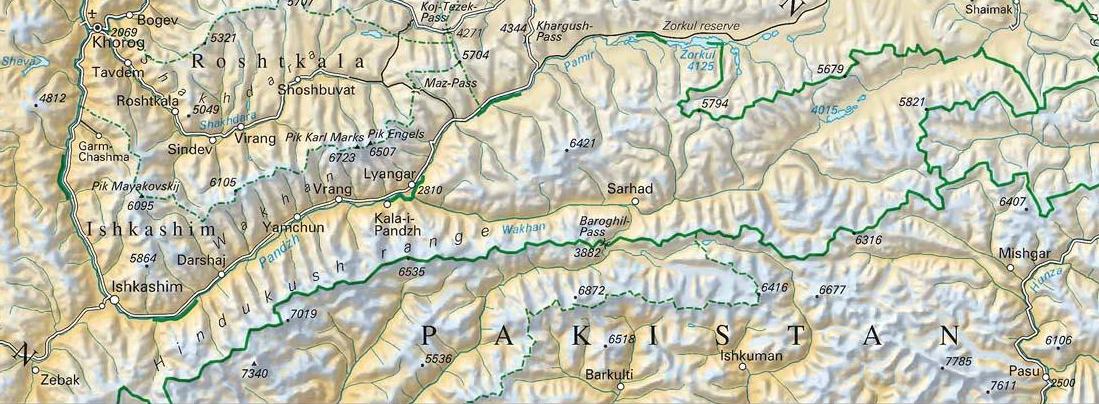

Sarhad is the easternmost permanent settlement of the Wakhan Corridor, the narrow valley that reaches out of northeast Afghanistan towards China. The corridor, about 220-miles long and 8-miles wide at its narrowest, is bordered by Tajikistan to the north, Pakistan to the south, and China to the east.

It is late July, 2011, and I have just spent a week walking in the surrounding mountains. Now, it is time to begin the journey out of the valley.

The Wakhan was created as a buffer between Czarist Central Asia and British India through agreements between Britain and Russia in 1873 and between Britain and Afghanistan in 1893. It was attached to the Emirate of Afghanistan, against the wishes of its ruler, who thought the area too isolated to be defensible. He was justified – the Wakhan sits at the junction of three major mountain ranges, the Hindu Kush, the Himalaya, and the Pamirs – what is called the Pamirian Knot. The valley is carved by the Wakhan River, fed by glacial meltwater from the surrounding mountains. From the town of Ishkashim, at 2,700 meters above sea level, the valley climbs steadily eastward, eventually reaching high altitude pasture land, above 4,000 meters, along the border with China.

Today, the Wakhan constitutes Afghanistan’s most remote region. On one hand, this seclusion has kept the area entirely peaceful. None of the warfare or American military occupation that pervades the rest of Afghanistan reaches here. On the other hand, this isolation, combined with the extreme elevation, means that life in the Wakhan is harsh and services are limited. Marco Polo described the eastern end of the Wakhan with these words as his caravan advanced up the valley:

The region is so lofty and cold that you do not even see any birds flying.

And I must notice also that because of this great cold, fire does not burn so brightly,

nor give out so much heat as usual, nor does it cook food so effectually.”

– The Travels of Marco Polo/Book 1/Chapter 32

Around 12,000 people inhabit the valley. The vast majority are Wakhi. They speak the Wakhi language, distantly related to Persian, and are Ismailis, a progressive branch of Shia Islam that eschews many conventional Muslim practices. They do not fast during Ramadan, for example, which is uncommon elsewhere in Afghanistan. The Wakhi practice combined mountain agriculture, growing wheat, barley, potatoes, beans, and peas in the valley, and herding their yak, sheep, and goat to high-altitude pastures above 4,000 meters during the summer. Their homes are made of stone and mud-plastered walls that are scattered around the valley floor around irrigated mountain oases. Those Wakhi that bring their animals to the high pastures live in nomadic yak-fur tents during the summer.

It took two days in the back of a pickup truck to reach Sarhad, located at 3,400 meters. The journey on the dirt track that pushes its way down the Wakhan Corridor from Ishkashim is humbling. The distances are vast.

Map of the Wakhan Corridor

At present, I have to make my way west towards Ishkashim. There is no public transportation to or from Sarhad. A couple cars a week make the journey, mostly NGO workers or foreigners on fully catered, heftily priced adventure tourism trips. Occasionally, a merchant truck comes from Kabul, selling clothes and wood for construction.

At present, I have to make my way west towards Ishkashim. There is no public transportation to or from Sarhad. A couple cars a week make the journey, mostly NGO workers or foreigners on fully catered, heftily priced adventure tourism trips. Occasionally, a merchant truck comes from Kabul, selling clothes and wood for construction.

Three Wakhi farmers on a hill near Sarhad.

I have no car but this is not a problem. I want to walk down the Wakhan. I want to spend time in the villages and feel the length of the valley with my own body. Ali Beg, the owner of the guesthouse I have been staying in, comes out to wish me goodbye. Before I take a picture of him, he dusts his jacket and Chitrali cap off, wipes his face with his hands, and repositions his cap.

Ali Beg, guesthouse owner in Sarhad.

I put my backpack on and start walking west. Two girls playing on the side of the track stop to look at me. They seem curious and nervous. I sense a slight tension and give them a smile and a wave. They meekly smile back, standing very close to each other. I say hello, and they remain silent. With a shy voice, one of the girls cries out “aks,” the Persian word for picture.

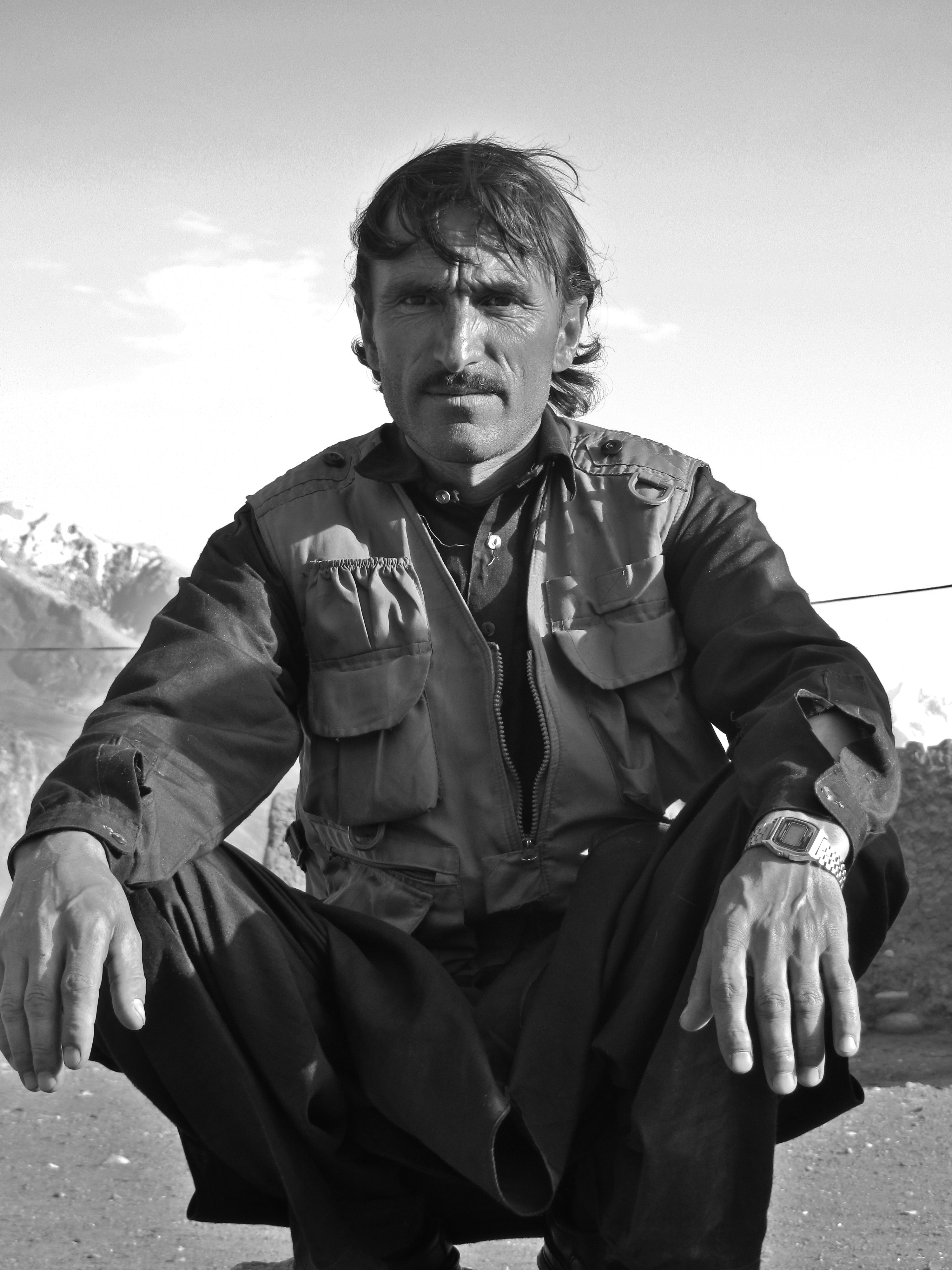

During my time in the Wakhan, I was frequently asked to take pictures of people I met while walking. Sometimes, I would ask them. I am attracted to portraits because they allow the viewer to look into another’s eyes and freeze that experience. Eyes reveal a common sensory experience, a shared interaction with the world, and this both relieves and perturbs me.

Farmer near Sarhad.

In many parts of Afghanistan, cameras are viewed suspiciously by locals who have grown weary of the intruding presence of outsiders, especially soldiers. Cultural and personal attitudes towards cameras can reveal a lot about a culture or person’s sense of self, curiosity, and relation towards foreigners, at a given time. In the Wakhan, where the violence of modern war and the US occupation are not quite felt, people are understandably more open and my camera was an invitation to conversation.

Schoolteacher in Sarhad.

As I reach the village of Chihil Kand, the sun is halfway through its descent. Due to the high peaks, darkness comes quickly in the Wakhan. A few of the villagers in Chihil Kand suggest that I rest here for the night. I am not in a hurry, but I decide to go on the next village, a couple kilometers ahead. I have more than enough time before nightfall. But I quickly run into streams and rivers. A number of meltwater streams trickle down from the mountains, occasionally forming rivers that I have to cross. I repeat the same process each time. I put my backpack down, take off my shoes and my socks, and place them in my backpack. I slowly wade across the freezing water. Balancing on one foot, I take the other foot and push it through the water, feeling the layout of the stones with my toes and finding a level spot. The water feels incredible on my aching feet. I sit down with my feet in the water. I take some and splash it on my face. I put on my shoes and keep walking.

I like walking because there are no shortcuts. Every rock, branch, and river is overcome personally. In each footstep one feels the scale of the land. Concentrating on each footstep, other thoughts disappear. I like the feeling of a footstep, of the different-sized rocks and pebbles sliding under my weight. They make a crunching sound as they rub against each other. The wind whirls around me. My backpack makes a creaking noise at each step. It is not the austere beauty of the landscape that quiets my mind. It is the act of focused movement through the unveiling landscape.

Eventually, with the sun skirting the top of the mountains, hiding and reappearing, I arrive at the village of Ptukh. A man welcomes me. We exchange the usual Afghan volley of greetings. Afghans, including the Wakhi, are fond of long formal greetings. I am led into a small guestroom – its walls and floor covered with dusty crimson-colored carpets. Like the central rooms of most Wakhi homes, this room has five wooden pillars supporting the ceiling. Some of the Wakhi claim the five pillars represent the five holy personalities of Ismailism.

Girl walking in Ptukh.

As darkness overcomes the valley, a small crowd enters the room, but only the adults speak to me. A meal of rice, bread, and tea is brought in. Six of us eat the rice and bread with our hands in silence.

I am exhausted. I drift to sleep amidst the occasional nighttime cry of goats.

Children walking in the riverbed.

A bit further, I am surprised to encounter a herd of Bactrian camels loitering near the river. The Bactrian camel has two humps, as opposed to its cousin, the one-humped dromedary or Arabian camel. The Bactrian camel was domesticated over four thousand years ago in northern Iran/Afghanistan, although they are supposed to be extinct in Afghanistan. There is no one around to tell me what they are doing here, but I imagine they are the proud descendants of the caravans which use to plow the Wakhan.

View across the valley as darkness approaches.

I turn my headlamp on. I am worried about walking at night. Any danger during the day – injury or bad weather – is more hazardous in the darkness of the night. Setting my apprehension aside, I cross the river on one of the valley’s few bridges and continue on a small footpath nestled between fields of barley. The moon casts a silver shine on the barley plants. The wind creates waves of crops – the plants crashing on the stone walls separating the fields. Walking uphill, I approach a cluster of houses. In the darkness, I yell in Farsi “Hello. Peace be upon you. I am a foreigner”. I hear some welcome shouts and a few quick steps, before a man pops out with a hand-cranked flashlight casting a dim glow. “Welcome” he says. Leading me to a new dusty room filled with carpets, we share our story. A crowd of children stand behind the doorway and a window, cautiously catching glimpses of the recently arrived night-visitor. A few of the children join us for a meal of rice, bread, tea, and a sweet, thick substance made of peanuts that is clearly a delicacy, judging from the look in the children’s eyes. A few village elders come join us and ask me for any medicine I have. I offer them paracetamol, but this they already have they tell me. “What kind of medicine do you want?” I ask. “For our backs. Our backs hurt” they answer.

My host in Khazget and his daughter.

I leave early the next morning. On my way out of the village, I notice a few of the men from last night sitting together on the side of a footpath.

The fields around Khazget I walked through during the night.

My early-morning burst of optimism subsides into a feeling of bodily fatigue. Ten days of walking at this altitude on a simple diet is slowly exhausting me. I reach a curve in the valley where the river’s waters churn into a mayhem of torrents. I pass by a group of Wakhi carrying shrubs used for herbal infusions. As I point my camera at them, I notice that they do not change their posture or expressions at all for the camera. They are the ones observing the camera.

I rest in the village of a Baba Tangi. I wait in the heat and practice English with a couple boys and girls, before filling up my water bottle and moving on. Before long, I have drunk all my water. Whereas before I could expect a stream of clean water every hour or so, I spend the next three hours with no clean water source. A slight numbness emanates from my forehead. I put my backpack down and sit on a rock. There is no shade in sight.

I arrive exhausted at the village of Qal-eh Wust. A man invites me into his large five-pillared Wakhi guesthouse. Like every other Wakhi home I have been sleeping in, I am not asked to pay any money for the food or meal. Some remuneration is generally expected by the hosts, but a tradition of hospitality makes many Wakhis abstain from demanding money. As dinner is prepared, I walk through the irrigated gardens, picturing in my mind the first settlers of the valley coming here. Who were the first inhabitants of this valley? Is the peace of the Wakhan worth the isolation and poverty? I have many thoughts but fall asleep.

When I get up, I hear a strange sound. It is the loud roar of a Kamaz truck, those powerful tank-like Russian trucks that lord over the roads here. The truck is driving down the valley, buying and selling livestock and grain from locals in what is essentially a moving market. They are going in my direction and I join the nervous, crying mass of animals in the back of the truck. They will be slaughtered and eaten in Ishkashim.

My view from the back of the Kamaz truck.

The going is slow. The truck stops at every village and hamlet. The seldom heard sound of the truck draws people from their fields and houses. A portion of the road has been carried away recently by high floodwaters. It forces the truck to drive over a farmer’s field. We wait a half-hour as the driver negotiates with the owner of a field for his permission to drive his crops. There is no other way to move forward. The road has taken a new path. The field owner gets paid a small amount for every vehicle that passes through his field.

Author passing an army checkpoint near Khandud.

By evening, we reach the Wakhan’s administrative capital, Khandud. The next day, I reach Ishkashim, the western end of the Wakhan. This town is inhabited by a mix of Wakhis and Tajiks. Ishkashim is a transition point between two worlds, between the peace and austerity of the Wakhan Corridor and the troubled mainland of Afghanistan. It is the gateway to Badakhshan, Afghanistan’s vast mountainous northeastern region, a major producer of poppy and cannabis, and home to the famous lapis lazuli. This is where my journey continues.

14 comments

Absolutely stunning.

Beautiful images and a wonderful recounting of an arduous journey.

Very impressive journey so well told. we are there in the story curious and apprehensive for the end. all details( history of the presence of camels, geographic precisions, cultural details….) add to the suspens; Is it not to much to be alone in such landscapes?

fabulous pictures that take you right into people’s eyes

This trip seems incredible and the pictures are stunning

Thank you for the wonderful post! Stunning and moving pictures!

These images are superlative. I am transported. What a journey and what people you encountered.

I look forward to the book!

amazing pictures… and shepard… just WOW! 🙂

amazing pictures and what a beautiful countery

Thank you for posting a wonderful experience that most people will never understand. As an American living in one of the neighboring countries, I salute you.

thank you. =)

MARVELOUS!

Hugs from Salvador de Bahia, Brazil.

Obrigado!