On the first of May, 1979, hundreds of thousands of Iranians poured out into the streets to celebrate International Worker’s Day. As a public festival created by the Second International to commemorate the 1886 Haymarket riots in Chicago, May Day became a holiday that was adopted by leftist organizations all over the globe.

Iranian left-wing groups began celebrating International Worker’s Day as early as the 1920s. Uninhibited after the departure of Reza Shah in 1941, many extant labor unions came together to form the Central Council of United Trade Unions (Shura-ye Motahedeh-ye Markazi) in 1944. In subsequent years, the labor movement continued to grow and May Day processions displayed the increasing power of a unified working class. During the height of Tudeh influence in the late 1940’s, May Day festivities in Tehran were attended by more than 80,000 people. However, the dominance of the labor movement was short-lived; following the coup d’état of 1953, trade unionism was virtually annihilated through bans and mass arrests. May Day processions would not be permitted until the final years of the Pahlavi era.

Free from the state repression of the Pahlavi era and well before the solidification of power under Khomeinist forces, the revolutionary period from 1979-1981 saw massive mobilization of the general populace. International Worker’s Day became an ideological battleground as competing political organizations—secular and religious—organized their constituents and articulated their interpretation of worker’s solidarity.

Visual ephemera related to May Day– posters, more specifically– are testaments to the pluralistic nature of the early years of the Revolution. By looking at various posters disseminated by organizations of the time, one can see how various political factions used similar visual motifs and iconography.

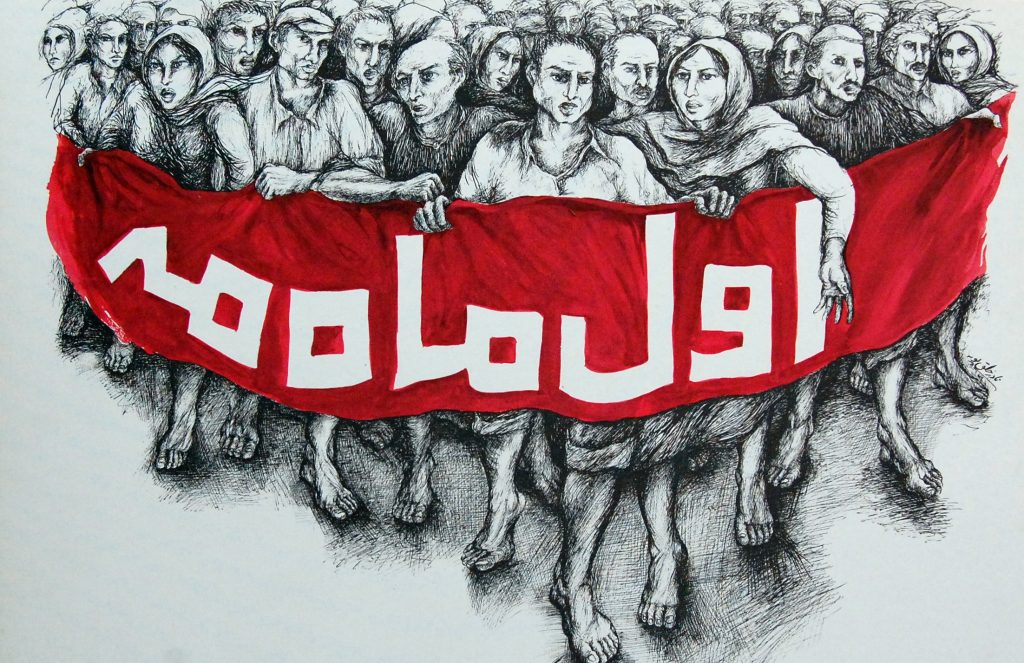

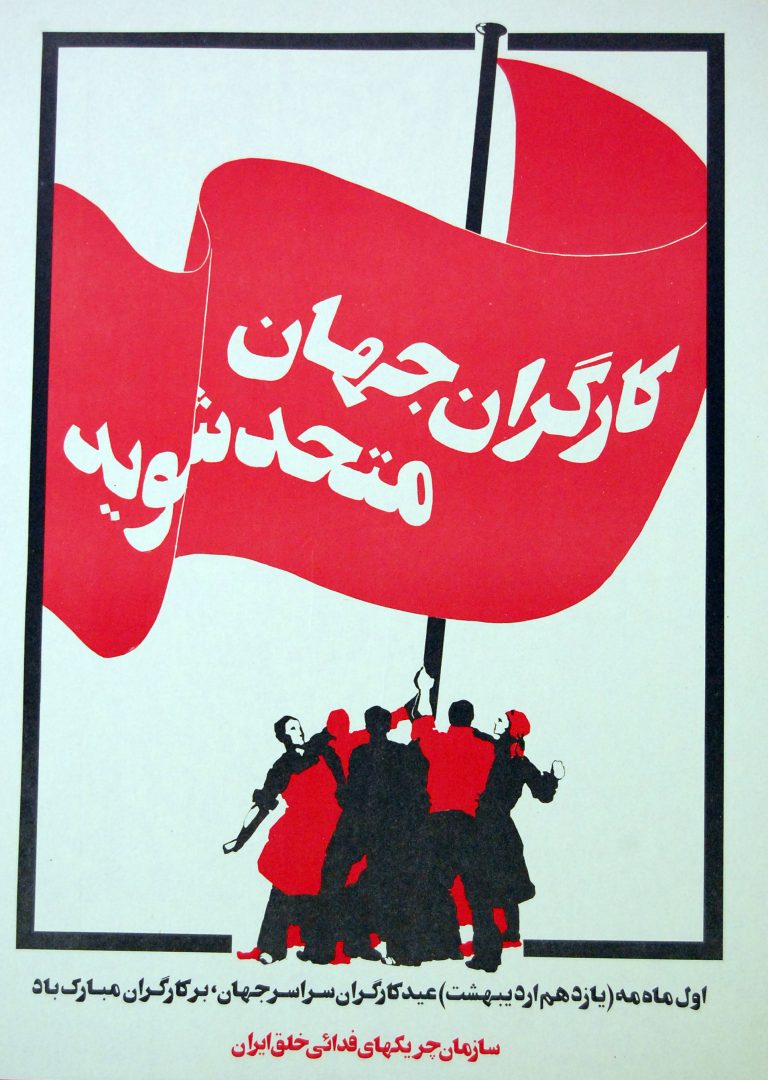

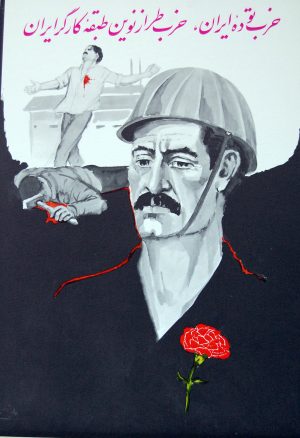

Iranian leftist organizations tried to connect Iran’s struggles to the rest of the international community through the glorification of the worker. In these posters, Marxist totems take the forefront; heavy machinery, proletarian caps, and smokestacks are depicted to celebrate traditional Marxism of industrialized society. Leftist May Day posters were specifically designed in a socialist realist style to emulate posters used by socialist movements, particularly those based in Europe and Latin America. Relying on internationalist symbols of the multitude allowed leftist organizations to communicate an idea of collective mobilization against the forces of capitalism and imperialism.

|  |

The first two posters portrayed were produced and disseminated by the Fada’i-e Khalq, a Marxist-Leninist guerilla group that began operations against the Pahlavi state in 1971. The poster on the left depicts a red clenched fist holding a bunch of tulips superimposed over a large gear. Industrial infrastructure such as factories, smokestacks, and an oil well are in the background. A gear, an essential component of industrial technology, acts as an index for all machinery and as an emblem for the principles of rationalism, precision, and standardization.

Similarly, the poster on the right champions the social realist aesthetic. It depicts a group of men and women working together to hoist a furling red banner. It is a narrative of a collective in motion, cooperating as a single unit to complete a specified task. The text reads: “Workers of the World, Unite.”— a direct translation of the most famous quote from the Communist Manifesto: “Proletarier aller Länder vereinigt Euch.” If one ignores the script, the poster could be comfortably placed on the streets of Berlin, Moscow, or any other city celebrating International Worker’s Day in 1979.

|  |

The posters above were created by the Tudeh party of Iran. Formed immediately after the abdication of Reza Shah in 1941, the Tudeh party was the oldest and most established leftist oppositional organization during the Iranian Revolution. However, by the 1970’s, Tudeh was only a shadow of its former self, due to effective suppression by the Shah’s intelligence agency, SAVAK. The poster on the left depicts a teary-eyed industrial worker mourning the deaths of his fallen comrades. Covering his heart, a lone red carnation– the “worker’s flower”– is pinned to his chest.

The right-hand poster portrays the union of industry and agriculture, a common trope in the European socialist tradition. These allusions to international socialism hoped to position Iran’s labor movement in the larger context of world revolution and worker’s solidarity. However, such styles could be alienating to the unfamiliar viewer, since the stylistic elements have not been adapted to the Iranian cultural context.

|  |

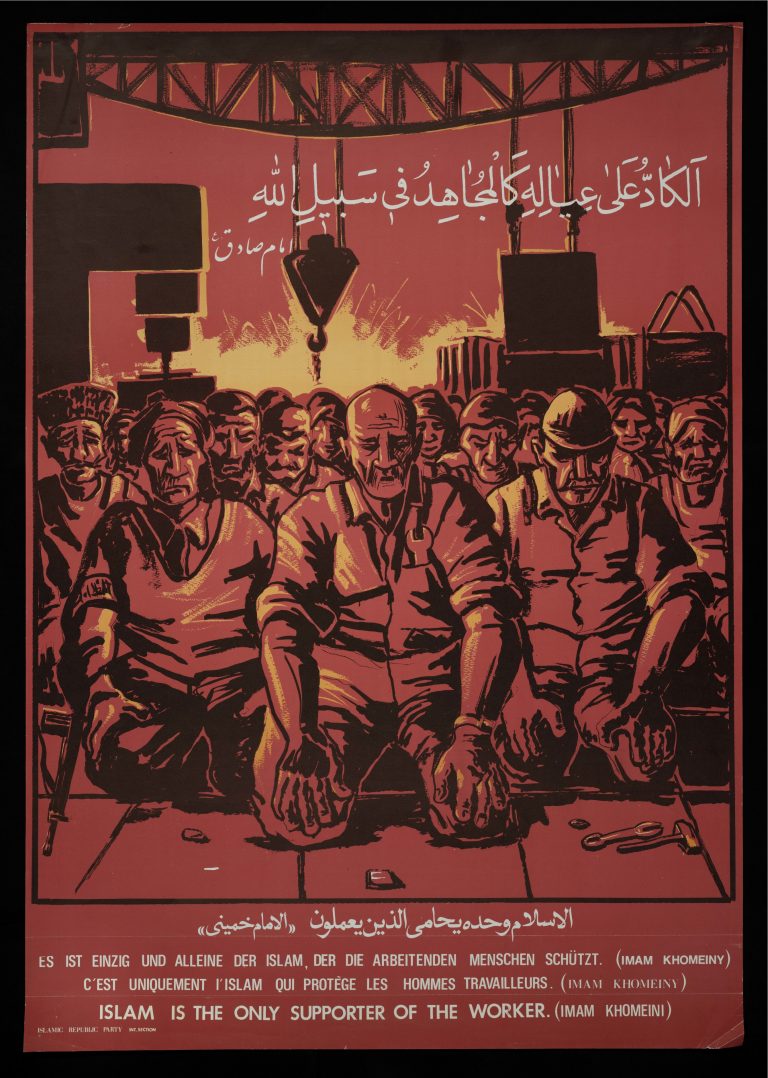

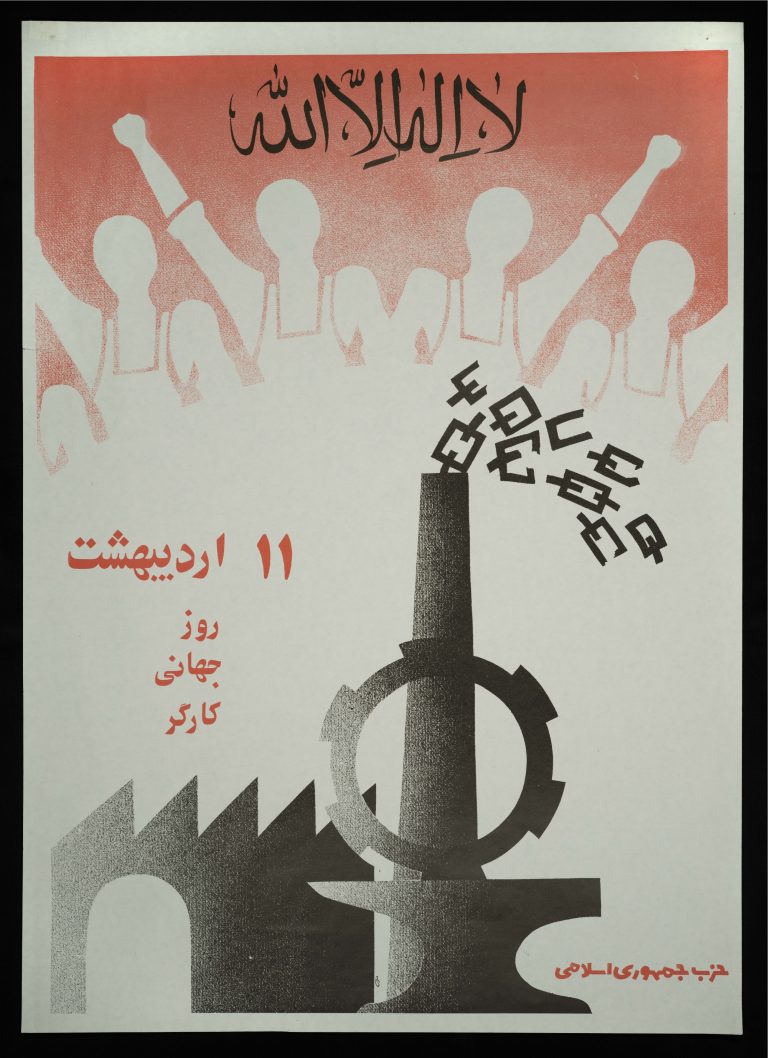

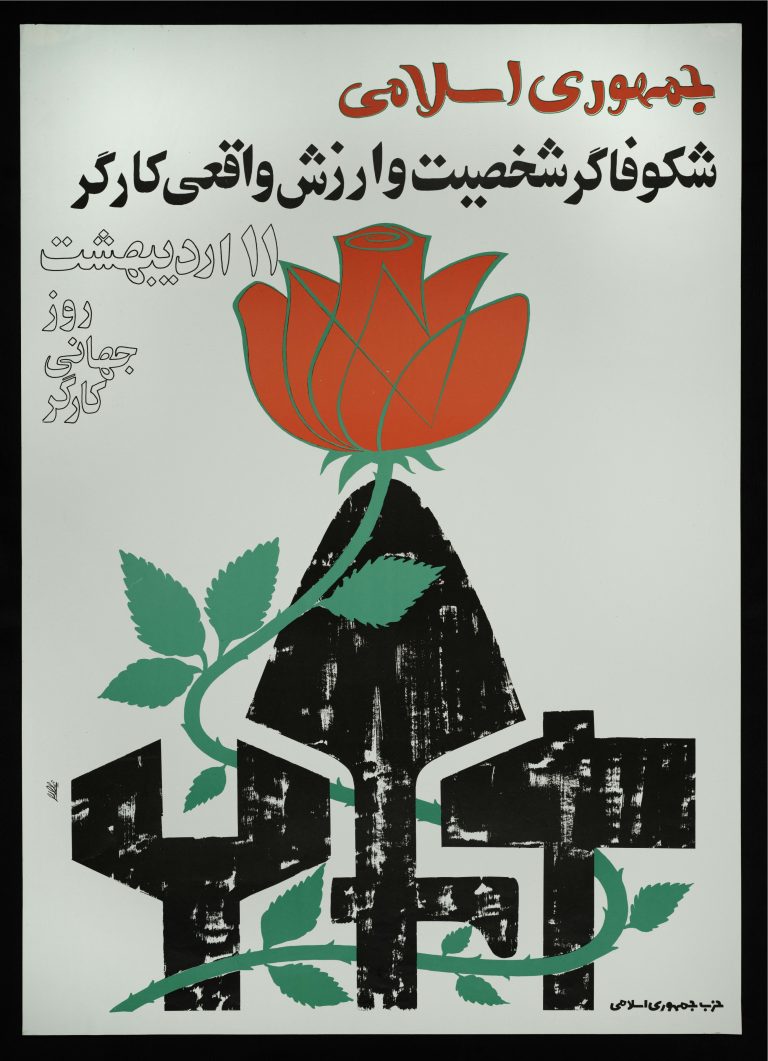

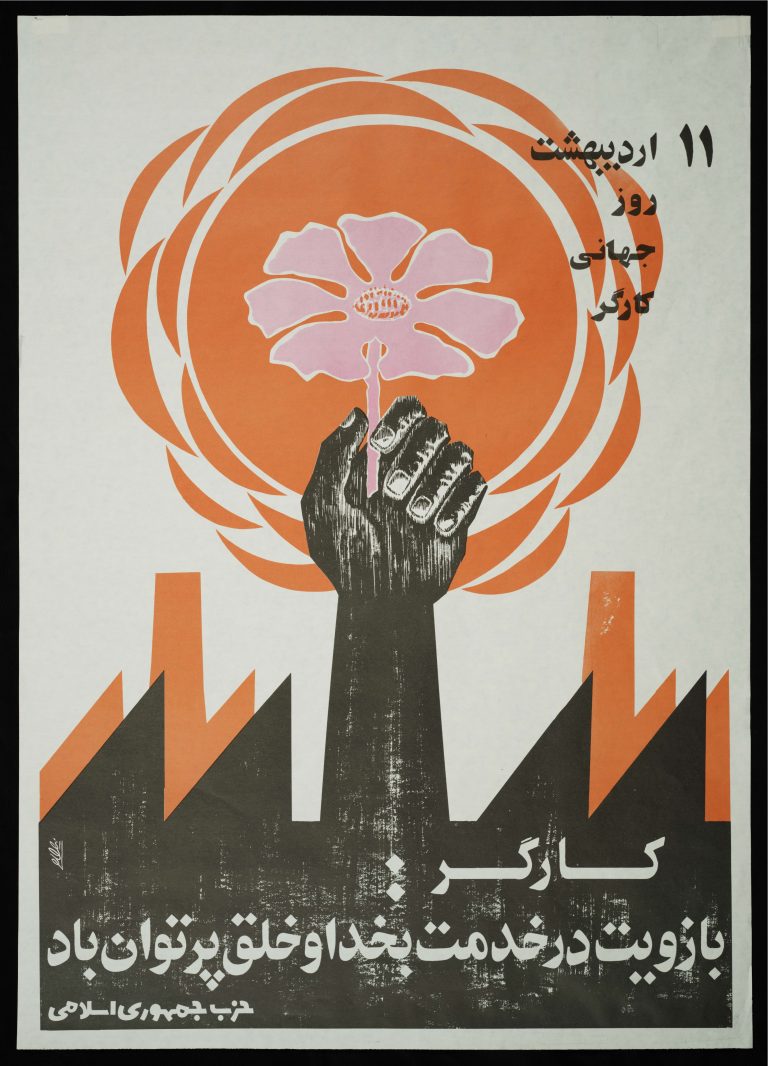

Surprisingly, Khomeinists adopted left-wing currents, rhetoric, and imagery from their radical secular rivals in order to “Islamicize” May Day. As opposed to leaving the symbolic power of May Day’s revolutionary potential to the secular leftists, Khomeinists sought to redefine it in an Islamic manner by adopting Marxist mass-oriented symbols. Drawing upon visual revolutionary rhetoric originating from international sources like clenched fists and the products of industry, the Islamic Republican Party coupled religious undertones with traditionally leftist visual motifs.

Qur’anic verses are a common addition on Islamic-oriented May Day posters. The inclusion of surat and naksh calligraphy constitutes a sacred certitude for the May Day poster. By synthesizing the iconography of the leftist tradition with divine textual messages, religious organizations successfully subsumed worker’s solidarity under a religious cosmology. The blending of various ideologies is a visual testimony to their flexibility and heterogeneity– utilizing religious, national liberationist, anti-imperialist, and even Marxist iconography to fashion a broad revolutionary (and sometimes contradictory) message.

|  |

By 1981, political organizations allied with Ayatollah Khomeini had politically outmaneuvered other oppositional groups. Nationalist and leftist parties such as the National Front and Fada’iyan (Majority) were banned and mass arrests were carried out. Furthermore, the revolutionary potential of May Day was contained by sedentizing celebrations into confined spaces such as university campuses and stadia. The holiday was eventually subsumed under a new name, “Workers’ and Teachers’ Day,” to commemorate the death of Ayatollah Motahhari. While International Worker’s Day is no longer celebrated as widely as before, the Iranian labor movement continues to be a driving force for change.

For more information, check out:

Middle Eastern Poster Collection at University of Chicago

Hoover Institution Political Poster Database at Standford University

In Search of Lost Causes: Fragmented Allegories Of An Iranian Revolution by Hamid Dabashi

May Day in the Islamic Republic by Ervand Abrahamian

3 comments

Fantastic, shared on FaceHook!