A native of Shiraz, Aria Fani is a doctoral candidate in Near Eastern Studies at the University of California in Berkeley.

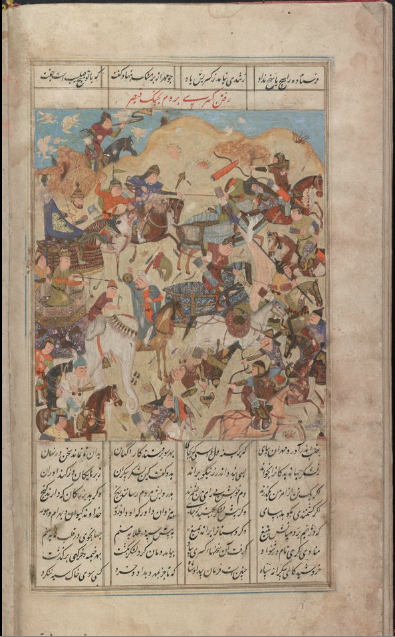

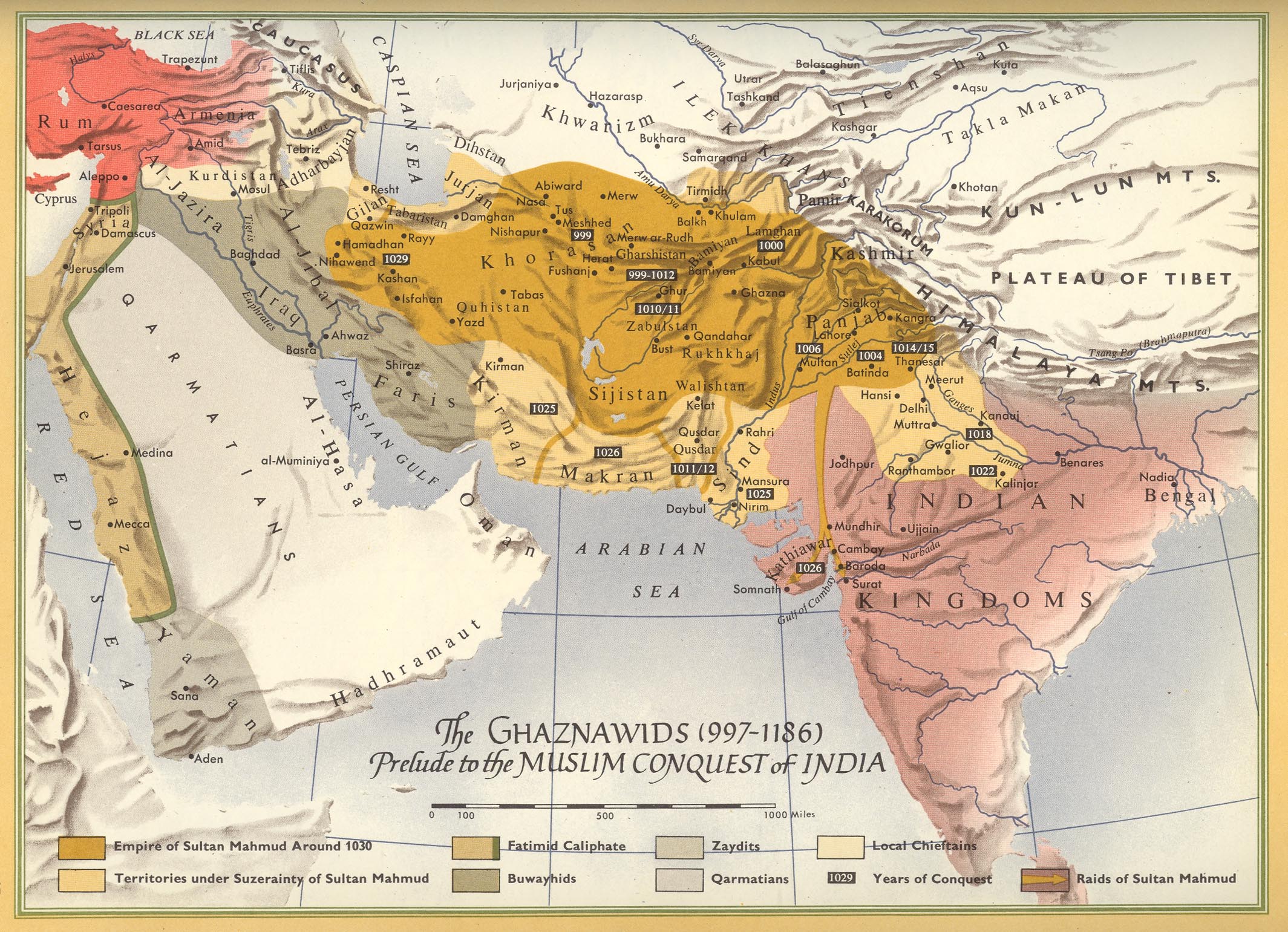

Today, we identify Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi as the national poet of Iran and his Shahnameh as its national epic. Ferdowsi lived in the latter part of the tenth century and the first quarter of the eleventh. He was a subject of the Ghaznavid empire, a Persian-speaking dynasty of Turkic lineage.

His era was marked by porous borders and shifting cultural and linguistic boundaries. Khorasan, Ferdowsi’s birthplace, was part of a cultural zone that stretched from the Bosphorus to the Bay of Bengal wherein Persian was a transregional language of literary production and cultural importance.

What does it mean then to speak of a “national” poet well before the advent of nationalism and certainly long before the formation of an Iranian nation-state in the first part of the twentieth century? The answer lies in the previous century during which Ferdowsi was cast as a national poet.

Ferdowsi the Tusi

None of the premodern accounts of Persian-language poets evoke Ferdowsi as an Iranian poet (or, variably, a poet from Iran). Nezami ‘Aruzi’s Chahar Maqaleh (The Four Discourses), composed in the twelfth century, is the oldest known account in which Ferdowsi’s oeuvre appears. ‘Aruzi introduces Ferdowsi as “one of the landowners (dehqan) of Tus,” and recounts the oft-cited story of Emperor Mahmud who failed to fully compensate Ferdowsi for the Shahnameh.

Dowlatshah Samarqandi’s Tazkerat ol-sho‘ara (Memorial of Poets), written in 1487, recounts the same story as ‘Aruzi’s Chahar Maqaleh, but also speaks of how Ferdowsi was tested by such court poets as ‘Onsori before gaining access into Mahmud’s poetic circle. Ferdowsi is again evoked merely as a poet from Tus. Taqi ol-Din Owhadi Balyani’s Arafat ol-‘asheqin va arasat ol-‘arefin (Arafat of Lovers and Parade Grounds of Gnostics), written in 1615, commemorates the work of 3,300 poets, including Ferdowsi.

The author of Arafat ol-‘asheqin introduces Ferdowsi as a poet from Tus and offers no reference to Ferdowsi’s belonging to a political entity called Iran. Reza Qoli Khan Hedayat’s Majma‘ ol-fosaha (An Assembly of the Eloquent), completed in 1868, is a Qajar-era compendia of 867 Persian poets. Its entry on Ferdowsi contains a curious (and inaccurate) story about how the manuscript that informed the composition of the Shahnameh traveled from Abyssinia to the Deccan and finally to Hendustan before it was brought to Ferdowsi’s native Khorasan. Even Hedayat, writing as late as the mid nineteenth century, does not characterize Ferdowsi as a poet from Iran. Each one of these sources is tied to its unique historical context which, while imperial and ecumenical, is not national. These documents reveal the way Ferdowsi has been viewed in different periods, but more importantly, they expose the fragility of taken-for-granted subjects like his “Iranian identity.”

As Dick Davis has shown in “Iran and Aniran: The Shaping of a Legend,” Iran as a geographical term in the Shahnameh varies significantly from a vaguely defined region to a unified territory ruled by a single king. The Iran of the Shahnameh is an unstable and changing geographical concept. Today’s Iran is a modern nation-state founded upon a nineteenth-century ideology that views language as the most definitive marker of a nation. The idea of the Aryan race, the attribution of perceived superiority to biologically predetermined factors, has been formative to the creation of Iran as a modern nation.

Persian Literature and Iranian Heritage

In the first quarter of the twentieth century, the relationship between state and society radically changed as the new Pahlavi regime set to align itself to a global model of “civilized” nation-states. This model had swept the imagination of most political elites around the world in the 1930s and 40s. During this period, Iranian historians and literary scholars, in conversation with their European and South Asian counterparts, began to rewrite their local history with Iran as its national subject. They also tailored their invented national history to fit a civilizational history. Mohammad ‘Ali Forughi (d. 1942), who served as Iran’s Prime Minister three times, paid close attention to the Persian literary tradition as a way of creating a cultural genealogy for an Iranian nation-state in the making. Forughi and his cohorts deemed Shahnameh a uniquely fertile text for their nationalist appropriation. In this process, they mapped their Iran, a political entity with defined borders, onto the Shahnameh’s incongruous geography.

In “The Nation’s Poet: Ferdowsi and the Iranian National Imagination,” Afshin Marashi has examined the way the Pahlavi elites used Ferdowsi in the service of nation building. He writes, “The fixing of Ferdowsi’s image and its association with the specific political project of Pahlavi nationalism was therefore something very new, never predetermined, and only one of Ferdowsi’s possible cultural-genealogical trajectories, a particular trajectory that was conditioned by the political history of the interwar period and by the cultural logic of nationalism during that time.”

Ferdowsi’s imagined place as Iran’s national poet was the product of intellectual and architectural labor sponsored by the state. In the first quarter of the twentieth century, the Pahlavi state began to produce and circulate images of Ferdowsi in film and media. His statues were erected in town squares, including one in front of the first Persian Faculty of Letters in Tehran. The Shahnameh became more accessible in illustrated, abridged, and simplified formats.

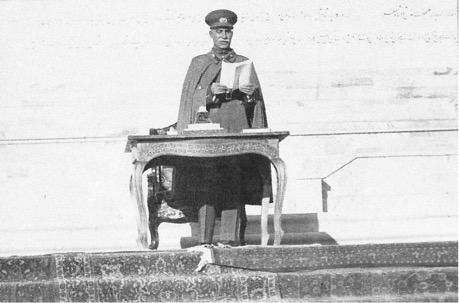

The attempts to enshrine Ferdowsi as Iran’s national poet were not limited to textual production. In the 1930s, the Pahlavi state became preoccupied with pinpointing the precise location of Ferdowsi’s burial. Once they claimed to have found his grave, the Society of National Heritage (Anjoman-e asar-e melli), a newly-established institution, built a mausoleum in 1934, modeled after Pasargadae, the tomb of Cyrus. In October of that year, Reza Shah (r. 1925-1941) inaugurated Ferdowsi’s mausoleum in a highly performative ceremony during which he thanked Ferdowsi for his services to the nation.

In Building Iran, Talinn Grigor has examined the history of the construction of the mausoleum as part of an effort to invent a site of collective national memory, one that drew its authenticity from the “precise” (invented) discovery of Ferdowsi’s burial site. The opening of the mausoleum occasioned a series of events in Iran and abroad that took place in the same year.

On November 8, 1934, Columbia University and the Metropolitan Museum of Art marked the thousandth birth year of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi. Many scholars gathered as “friends of Iran and lovers of her arts and letters” to commemorate the legacy of the “eminent Iranian poet.” There was a reception on campus, an exhibition of rare manuscripts of the Shahnameh, and four addresses by the chancellor of the university, scholars of Near Eastern arts and literature, and Iran’s top diplomat in Washington. Mirza Ghaffar Khan Djalal, the Iranian ambassador to the United States, began his address by remarking that “art and literature have no nationality.”

Ferdowsi the Aryan

Having spoken of Ferdowsi’s civilizational stature, Khan Djalal then evoked the Persian-language poet as the native of a land “called by all the cradle of the Aryan race,” whose verses have helped restore “unity among the Iranian race.” He celebrated Ferdowsi as a poet who revived Iran’s “national language” and reminded Iranians who had “forgotten all that meant national pride and glory” of their country’s “glorious past and civilization.” The ambassador concluded his remarks by praising his own patron, Reza Shah Pahlavi, who has already achieved great results in his unbending determination to restore as much as possible of the past Iranian glory, and, in order to render Ferdowsi’ memory eternal, has ordered the erection of a befitting monument for him and caused the celebration of his anniversary to be a national holiday.

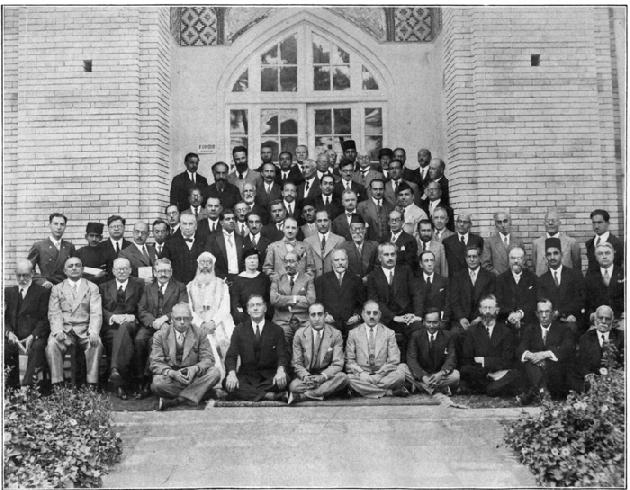

The celebration at Columbia University was one of many that took place around the world in 1934, including a month-long conference during September and October in Tehran. A group of Iranologists and Persian literary specialists was invited from fifteen countries by the Ministry of Education as guests of the Iranian state to travel in the country for thirty days. Organized by Hassan Isfandiyari, the first of seven meetings was held on September 29, 1934, at the auditorium of Dar ol-Fonun high school in Tehran and was attended by eighty three scholars. A selection of the addresses and speeches delivered during the month-long ceremony was later published in Tehran as The Millennium of Ferdowsi: the Great National Poet of Iran. The volume includes a picture of the young monarch, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and an image of the poet’s statue which was increasingly in circulation in the 1930s.

In his remarks, Mohammad ‘Ali Forughi said that Ferdowsi may be “physically bound to connections with Iranian-ness,” but he is “spiritually a child of humanity or if I may say, a father of humanity.” Forughi’s remarks, uttered in the same vein as Mirza Ghaffar Khan Djalal’s speech in New York, reflect the ethos of the Iranian project of nation-building: laying claim to Persian as an Iranian cultural patrimony while promoting it as part of humanity’s civilizational heritage. The millennial celebration of Ferdowsi is by no means the only example of the Pahlavi project which was designed to secure Iran’s place within what the elites deemed a league of “civilized nations.”

Ferdowsi the Afghan

It was not only the Pahlavi elites who actively sought to invent a distinct literary genealogy in the service of nation-building; Afghan intellectuals took similar steps in laying claim to the Persian literary heritage to define its Afghan character. In the 1910s, Mahmud Tarzi (d. 1933), an intellectual, publisher and modernizer, began theorizing what it meant to speak of an Afghan national literature. These discussions took place in the pages of his newspaper Seraj ol-Akhbar Afghaniyah (The Torch of Afghan News, 1911-1918). In the 1930s and 1940s, the Afghan state, like neighboring Iran and India, helped establish institutions like the Kabul Literary Association (1931) and Afghan Historical Society (1942) to create an Afghan literary and historical genealogy.

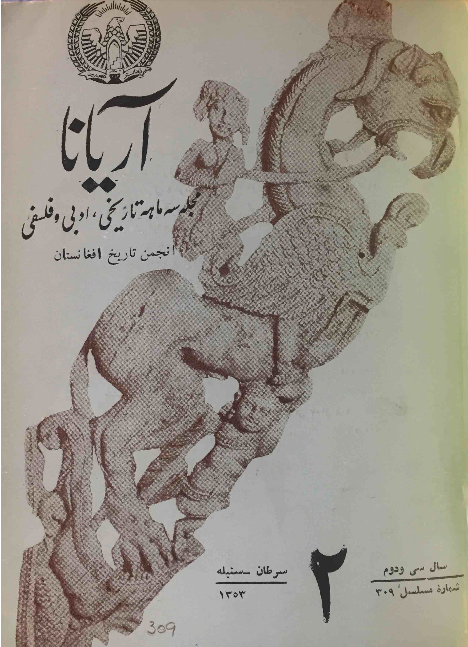

The president of the Afghan Historical Society was Ahmad ‘Ali Kohzad (d. 1983) who also served as the curator of the National Museum in Kabul. In conversation with archaeologists at La Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (DAFA), who made consequential discoveries in Afghanistan, Kohzad participated in creating an official historical identity for Afghanistan. One of the ways in which he worked towards that goal was editing the journal Aryana (founded in 1942), a term he used and promoted to refer to ancient Afghanistan.

In his Afghanistan dar Shahnameh (Afghanistan in the Shahnameh), published in 1976, Kohzad employed his archeological knowledge and newly constructed historical model to tease out elements in the Shahnameh that he viewed as Afghan. From the outset, he admitted that the term “Afghanistan” is new and does not appear in the Shahnameh. If one carefully examines the names of cities and regions in the Shahnameh, he claimed, one would realize that its geography largely corresponds with Khorasan, which Kohzad called ancient Afghanistan. Kohzad celebrated the place of Afghanistan in the Shahnameh as a way of making visible his homeland’s contributions to Persian literary culture and bolstering the civilization credentials of Afghanistan.

Kohzad’s work, similar to the Pahlavi elites in Iran, maps a modern political phenomenon, Afghanistan, onto the geography of the Shahnameh. Kohzad also credited the poet Abu-Mansur Daqiqi (d. 1005) for laying the foundation of the Shahnameh with his tales of and literary lore. Kohzad celebrated Daqiqi as a poet from Balkh, a region in Afghanistan. In 1975, Kabul organized an international conference to celebrate the work of Daqiqi which led to the publication of several books like Kohzad’s Afghanistan dar Shahnameh. Making visible Ferdowsi’s debt to his predecessor Daqiqi, both from Khorasan, was part of broader efforts in Afghanistan to reinvent and appropriate the Persian literary heritage.

Many Iranians may quickly dismiss Kohzad’s assertions. For them, Iranian national identity is authentic and valid while other national identities, be it Afghan or Turkish, are novel, invented, and therefore false. Similarly, they would view the borders of Afghanistan as new and fabricated while Iran for them has always existed in its current location. If there is a major takeaway from this article is that there is no such thing as always in history. Iranian national identity, a pillar of which is Ferdowsi and his Shahnameh, is just as (if not more) invented as Afghan national identity. The fact that they are constructed identities does not make them false or inauthentic. What other tools do we have as humans besides the power to imagine and create, to make meaning? But unless we realize the invented nature of our national identity, we will not be able to consciously participate in remaking it in the image of our own values and ideals. That realization begins with a critical understanding of history.

The late nineteenth and twentieth century was a period during which new institutions of political power and literary production displaced older formations of identity. The nation-state as a political model gradually became the norm and drove countries like Iran and Afghanistan to fashion themselves as modern nation states by inventing a distinct cultural genealogy. To gain entry into what they perceived as a league of civilized nation-states, Iranian and Afghan intellectuals set out to excavate the Persian literary tradition in search of texts and tools to construct new identities. It was in this process that Iran imagined Ferdowsi as its national poet. Afghan intellectuals, aware of such developments in Iran, responded by articulating their own claim to the Shahnameh and Persian literary culture. Ahmad ‘Ali Kohzad’s Afghanistan dar Shahnameh is only one example of such effort.

Although nationalism championed an inward search for an “authentic” identity unique to a particular people or race, its universalized model became a common language that took inspiration from many different cultures. The millennial celebration of Ferdowsi in Tehran in 1934 brought together scholars from more than a dozen countries whose scholarship shaped the way Iran imagined Ferdowsi as its national poet. This quality may point in the direction of an inherent contradiction in nationalism: the expression of national identity may be local, but the ideological forces that inform its expression are transnational.

Everchanging Nationalism

Many Iranians today no longer associate Ferdowsi with the Pahlavi state and its efforts to frame him as Iran’s national poet. The Islamic Republic, as Grigor has shown in her excellent book, may have partially erased the trace of Pahlavi patronage at Ferdowsi’s mausoleum in Tus; nonetheless, it has conveniently received a ready-made site of national memory visited by thousands of Iranians every year. One may argue that the Pahlavi elites achieved their ultimate objective by co-opting Ferdowsi as the national poet of Iran, a fact that remains contested as evident in Kohzad’s Afghanistan dar Shahnameh.

To treat Ferdowsi’s idea of Iran as a timeless and unchanged concept is to pretend that none of the political and cultural developments of the twentieth century ever took place. My aim here was not to reject or validate the notion that Ferdowsi is Iran’s national poet; my objective is to historicize and place it within its early twentieth-century context. I do so with the hope that we may problematize the work of political elites, literary scholars, and architects in the 1930s and 1940s who helped remake Ferdowsi in the image of their cultural ideology and political ideals.

This article was previously published in the January-February issue of Peyk, the San Diego-based Persian Cultural Center‘s magazine.

References:

- Mohammad A. Forughi. Kholaseh-e Shahnameh-ye Ferdowsi (Tehran, 1935).

- David E Smith. Firdausi Celebration, 935-1935: Addresses Delivered at the Celebration of the Thousandth Anniversary of the Birth of the National Poet of Iran Held at Columbia University and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the City of New York (New York: McFarlane, Warde, McFarlane, 1936).

- The Millennium of Ferdowsi, the Great National Poet of Iran [with Plates.] (Tehran: Vezārat-e Farhang, 1944).

- Dick Davis, “Iran and Aniran: The Shaping of a Legend.” In Iran Facing Others: Identity Boundaries in a Historical Perspective. Ed. Abbas Amanat and Farzin Vejdani (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 39-50.

- Afshin Marashi, “The Nation’s Poet: Ferdowsi and the Iranian National Imagination.” In Iran in the 20th Century: Historiography and Political Culture. Ed. Touraj Atabaki. (London: I.B. Tauris, 2009), pp. 93-111.

- Talinn Grigor, Building Iran (Periscope Publishing, 2009).

- Ahmad A. Kohzad. Afghanistan dar Shahnamah: Shahnamah dar Khorasan, ya, Shahnamah dar Aryana (Kabul: Bayhaqi Ketab Khparawulo Muʼassasah, 1976). For more on Kohzad, see Nile Green, “The Afghan Discovery of Buddha: Civilizational History and the Nationalizing of Afghan Antiquity.” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 49 (2017), 47-70.

10 comments

Yet again we see Ajam Media trying to discredit Iranian heritage and culture. Ferdowsi’s composition of the Shāhnāmeh was his attempt to protect his people’s (which includes Afghans) ethnic identity by preserving Iran’s national lore.

I love the fact that your academic engagement with this piece is limited to the use of diacritics in the word Shāhnāmeh. We are indeed making progress!

I also love how Iranian nationalism conveniently co-opts Afghans as “part of our people” when it suits one argument and vilifies them as savage outsiders (in the case of the Afghan invasion of post-Safavid Iran) to bolster another.

Just another empty nationalist talking point.

Ebrahim, Your comment is not any better, if not worse. Also Tous is still in Iran. If you use geographical locations to say from what countries these poets were from, then by that logic Ferdowsi is from Iran (like some Afghans say Rumi is their poet). Also how do you know the original commenter is talking about Afghans like that? Who is next? Next time I need to hear Saadi and haves are not Iranians and they were originally from Afghans.

“Just another empty nationalist talking point.” You are doing the same, judging by this comment of yours. I admit I have done the same by replying to your comment

What is Iranocentrism in modern Persian studies? (And by Iran I mean modern Iran – nation state)

Irano-centrism is not only about giving disproportionate interest to the territory of modern Iran in the study of the history and civilisation of all Iranic and Persianate peoples ignoring most of the things that remain beyond the borders of modern Iran. This is Irano-centrism in its crudest form.

It is also about fitting the entire cultural domain of the Persianate world into the modern geography of the Iranian state. Ironically, this is the very notion that the author of the article sets to criticize but nonetheless falls into the same trap by ignoring the entire geographical region of Transoxiana (Mawaraunnahr) that gave impetus to the new Persian language and literature and personally to Ferdowsi!

And this is not the major problem with the article. The author can be forgiven for not going into the details of Ferdowsi’s world, for not mentioning the Samanids, Mawaraunnahr and Bukhara even a single time, since she is apparently talking about the use and abuse of Firdawsi in the modern Persianate world.

The main issue is indeed her ignoring the modern Persianate world and the place of Ferdowsi in it. I will not mention the cases of Azerbaijan, Armenia and Uzbekistan, but one could argue that not only was the modern Tajik nation founded on the shoulders of Ferdowsi, but also the entire modern Tajik literature is a footnote to Ferdowsi. It does not stop with literature but also continues with art, theatre, film etc. As far as I know, Tajikistan is the only country that produced films based on Shahnameh and the life of Ferdowsi and other literary figures such as Rudaki and Ibn Sina among others. (this paragraph can be expanded and published as a book).

That the author has paid some attention to Afghanistan is commendable, but the picture is far from complete. When Ferdowsi and his Shahnameh are deployed against the idea of Afghan national identity in Afghanistan by Persian speakers, the article doesn’t make much sense. It would be great to see a real comparative case i.e. the role of Ferdowsi in early Soviet Central Asia where Ferdowsi and Rudaki saved Persian from destruction yet another time, this time against Stalin.

My contribution to Persian studies is only rant.

Thank you for reading the article and taking the time to share your critical thoughts. I appreciate it.

I won’t get into all your points, but will broadly say this: here, you’ve adopted the same language used by Iranian nationalists, but with the objective of combating it as opposing to validating it. You may think you’re challenging Iranian nationalist myths, but you’re standing within the same epistemic circle as Iranian nationalists when you fetishize the literary production of Transoxiana (“the entire modern Tajik literature is a footnote to Ferdowsi” (?!!).

My friend, my goal here was not to show that Ferdowsi belonged to one region more than the other. My objective was to place two nationalist literary projects side by side to show that even when their claims are in contestation of one another, the idiom with which they lay their claim to Ferdowsi draws on a shared world of references and tools. They are within the same epistemic circle.

I frequently meet well-intentioned Iranians and Afghans who think they are doing the rest of the Persian-speaking region a favor by speaking combatively with Iranian nationalist claims in its own language. Alternatively, we could to take a step back and view these nationalist projects transregionally – not to adjudicate which one is more historically authentic – but to critique the nationalist idiom with which they were all engaging in one way or another, whether they were in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, India or elsewhere.

I am humbled by how much there is to read and how much rethinking is involved in this process. So, I would appreciate any critique of my methdology. But you’ve let me off the hook easily here.

Dear Aria,

Thanks a lot for replying and apologies for the criticism, which was partly unfair, since you are one person who disapprove of Iran-centrism. It wasn’t a well-thought reaction, but a Facebook post that received some attention from friends – Iranists, so I thought it was worth sharing here as well.

There is a misunderstanding, however. I had no intention to fetishize the literary production of Central Asia, neither to justify the region’s claim to Ferdowsi, no to glorify anything. What I wanted to point out was that Ferdowsi’s work played a much greater role in Soviet Tajik nation-building, which is within the topic and time period under discussion in your article. Yet you fail to bring this in, which puzzles me since it would have demonstrated how Ferdowsi’s ideas were simultaneously used to justify monarchy, Soviet realism, Marxist class struggle and so on and so forth in the wide Persianate world. Instead, you look at Afghan nation-building, which as you know, is Persophobic and increasingly Iranophobic and Ferdowsi doesn’t play a major role in it.

As for Soviet Tajik nation-building, it is a different story. The existence of the nation or rather the right to build a nation was premised upon speaking a distinct language (Persian), which was “proved” by Sadriddin Ayni whose anthology ‘Namuna-i Adabiyat-i Tajik” (1925) became the main argument for forming the Tajik nation-state. With the main cultural centres left outside of its borders, literature became the main anchor for romantic nationalism and nation-building. By saying “modern Tajik literature is a footnote” to Ferdowsi, I am not fetishizing anything, I am just pointing out the paramount influence of Ferdowsi on Tajik Soviet literature.

I agree with your argument and your conclusion. The only issue is that the article talks about Ferdowsi and nation-building projects of the early twentieth century and limits the discussion to Iran and Afghanistan. Uninformed readers will assume that Ferdowsi is known or celebrated in these two countries only. That’s why Iranians usually ask Tajiks “Farsi kojā yād gereftī.” They can’t be blamed because that is what they learn at school. Unfortunately, this particular article of yours doesn’t give any clue to those readers.

I hope I made my views clear.

Thank you for your thoughtful response, I better understand your point of view now. I do agree that the Tajik case is particularly rich. I didn’t include the Tajik case because I don’t feel confident about my command of Tajik literary historiography and because my friend Sam Hodgkin in Chicago has done a thorough job writing about the development of a modern Tajik literary canon in the multilingual Soviet zone in his doctoral dissertation. We all have to wait for his book in the coming years.

This article does not imply in any way that Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh played a role in nation-building *only* in Iran and Afghanistan. If anything, because of its comparative case, it will generate dialogue about all the other post-Persianate nation-states (if we can call them that) in which the Shahnameh has played a major role. Our dialogue is an example of that.

I don’t agree that the Afghan nation-building project has been Persophobic. I don’t think it has had one ideological strand in relation to Iran to begin with. The Afghan nation-building process has developed in dialogue with those of Iran and all other countries in the region. Some of those dialogues have been contentious, but I wouldn’t call it Iranophobic, certainly not in the first half of the 20th century. Persian has been an integral part of Afghan nation-building and in some monumental ways has determined the trajectory of Pashto and its social domain in Afghanistan and beyond as well.

In order to highlight the ways in which the Shahnameh became a key text in the formation of a modern Soviet Tajik literary culture, we don’t have to quantify its importance in relation to Iran or Afghanistan. That I find problematic.

I appreciate your critical sentiment toward the absurd and false idea that somehow to speak or write Persian well, one had to have been born and raised in Iran. And I was one of those Iranians who would have asked, “Farsi kojā yād gereftī.” I came to the U.S. and thanks to its liberal education and academic resources, I learned about the historical routes of Persian in ways that may not have been possible in Iran.

Thanks a lot for your elaborations. Actually, one of the people who engaged with my post, an American who studies in Iran says that he found his Iranian university less Iran-centric then the US schools. I won’t go into this here.

Thanks for mentioning your friend’s dissertation, I will try to find his work and critical studies by other people and explore this topic more. Your information regarding Afghanistan is limited to a few examples from the later period, it is definitely worth digging more into the early period.

I think quantifying and measuring the importance of one text or one author makes sense. Consider this comparison: Iran had historical capitals, royal dynasties, a ruling dynasty, historical state institutions, BORDERS and many more texts (Qazwini’s “Tārīkh-i muluk-i ʿajam” is a case in point) and authors who could significantly be transposed into the national context. Tajikistan had none of those. Borders were imposed and contested, historical cities lost to another newly founded country, state institutions didn’t exist, a country was literally built on the basis of having a literature. But not all poets and writers were acceptable in a Soviet context. Rumi hardly made it to any textbook, Nāsir- Khusraw was deemed a reactionary religious fanatic, same goes for most Sufi poets and people of religious occupation. Ferdowsi was among the few acceptable pro-proletariat poets, also a subject of the Samanid, whose work was a lot easily interpreted and used for nation-building purposes than that of Rudaki and Ibn Sina, two other ‘local’ Central Asian “Tajik” giants. Thanks again for replying.

Very useful post. This is my first time i visit here. I found so many interesting stuff in your blog especially its discussion. Really its great article. Keep it up.

I say Ferdowsi in fact belongs to any person who speaks Persian and loves the language. And not just modern day Iran. But mostly ancient Iran which is not just modern day Iran and Afghanistan.