When I was in Iran last summer, I faced a series of realities that moved me in a fundamental way. First, I realized that the landscape in Iran changes so quickly that the next time I visit, I will likely end up navigating new streets and neighborhoods that haven’t yet been built. Second, I realized that Trump’s increasingly vitriolic rhetoric will make travel to Iran more difficult in the future. Just a few months before my visit, the Muslim Ban had halted a massive amount of travel, and the subsequent iterations of the ban continue to demonize immigrants and travelers to the US for their country of origin. With the talk of war on the horizon, the ability to travel seems increasingly clouded by uncertainty. Third, and most devastating, I knew that some of the people I love the most won’t be there the next time I visit them.

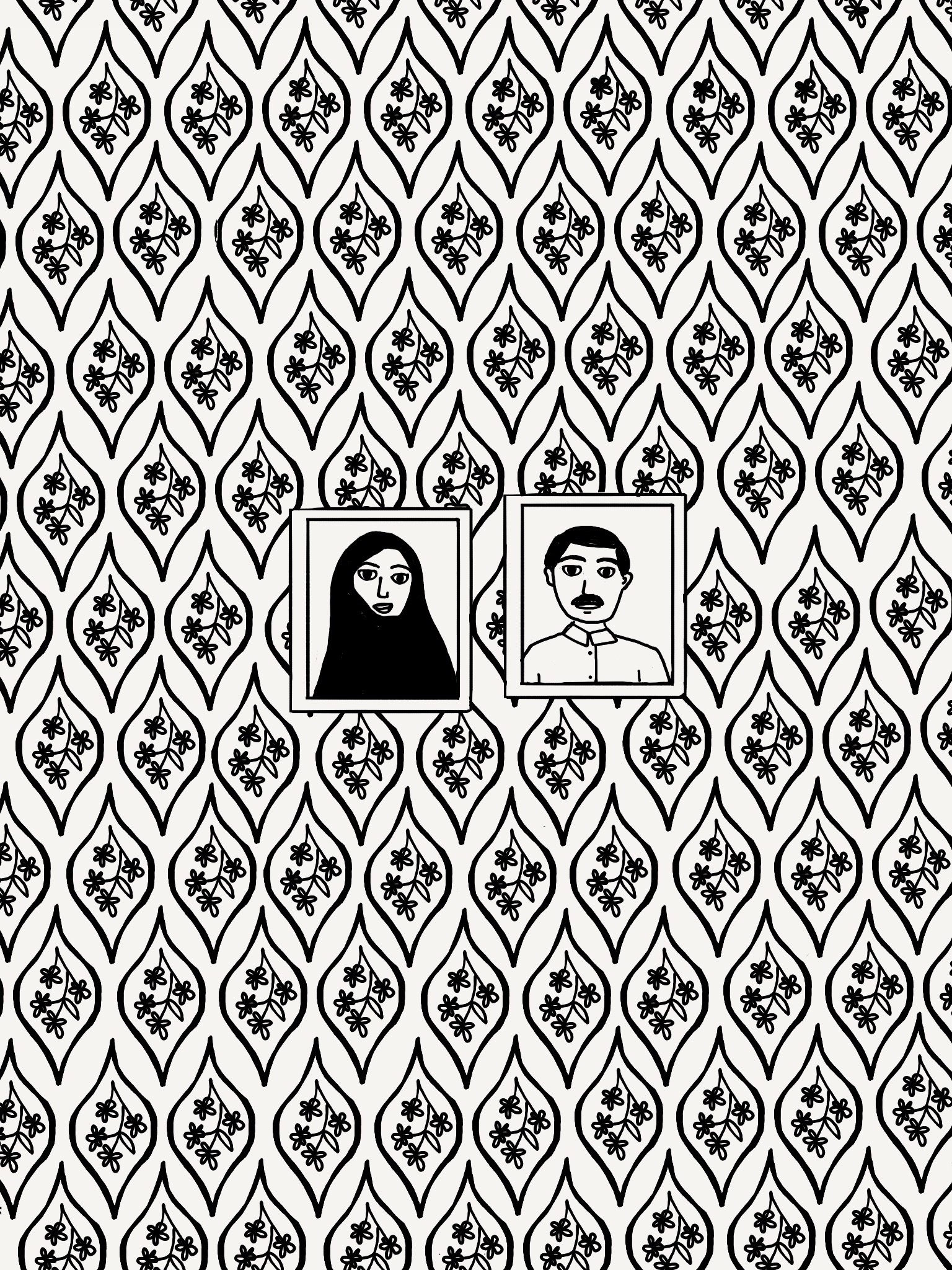

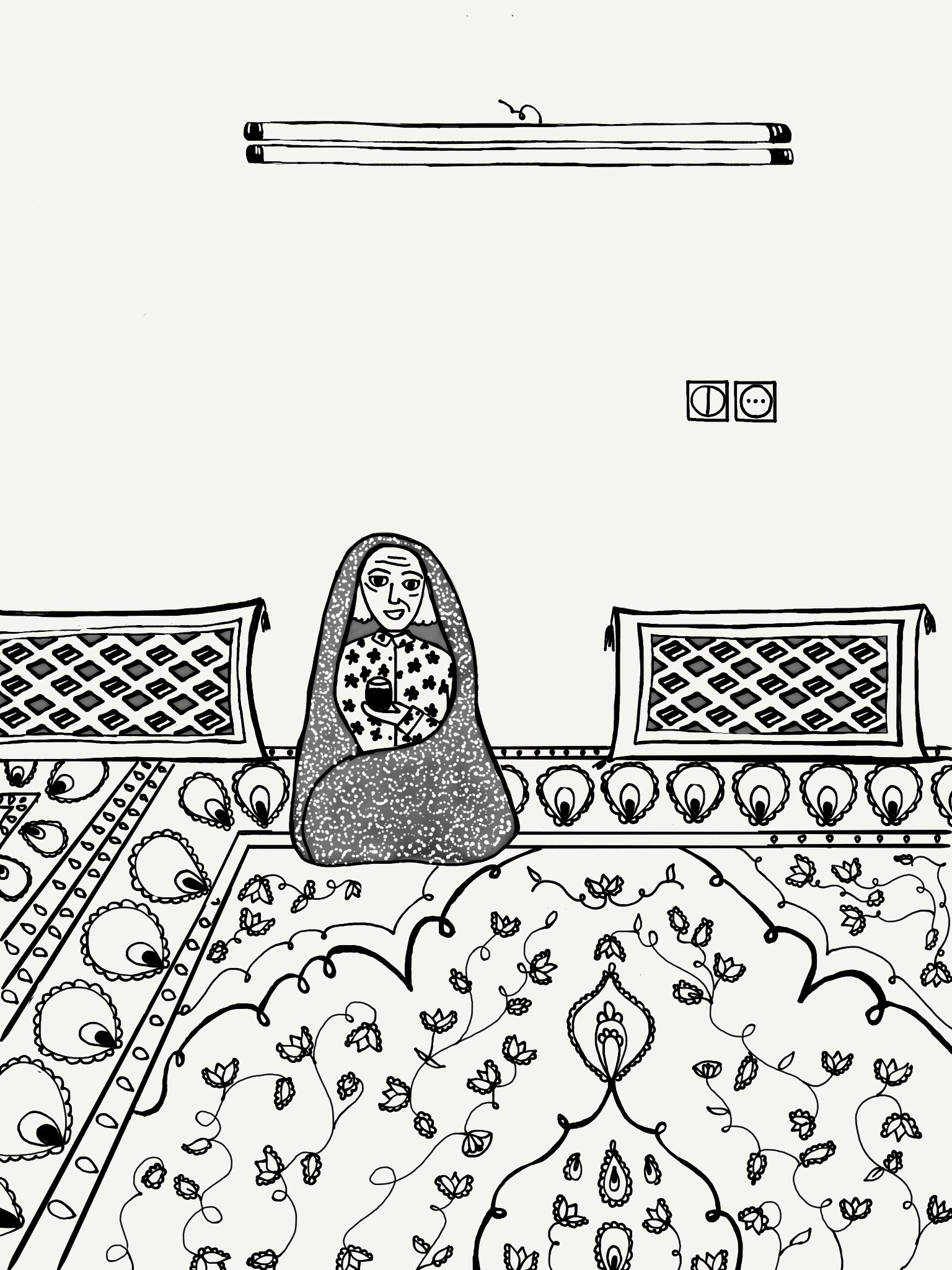

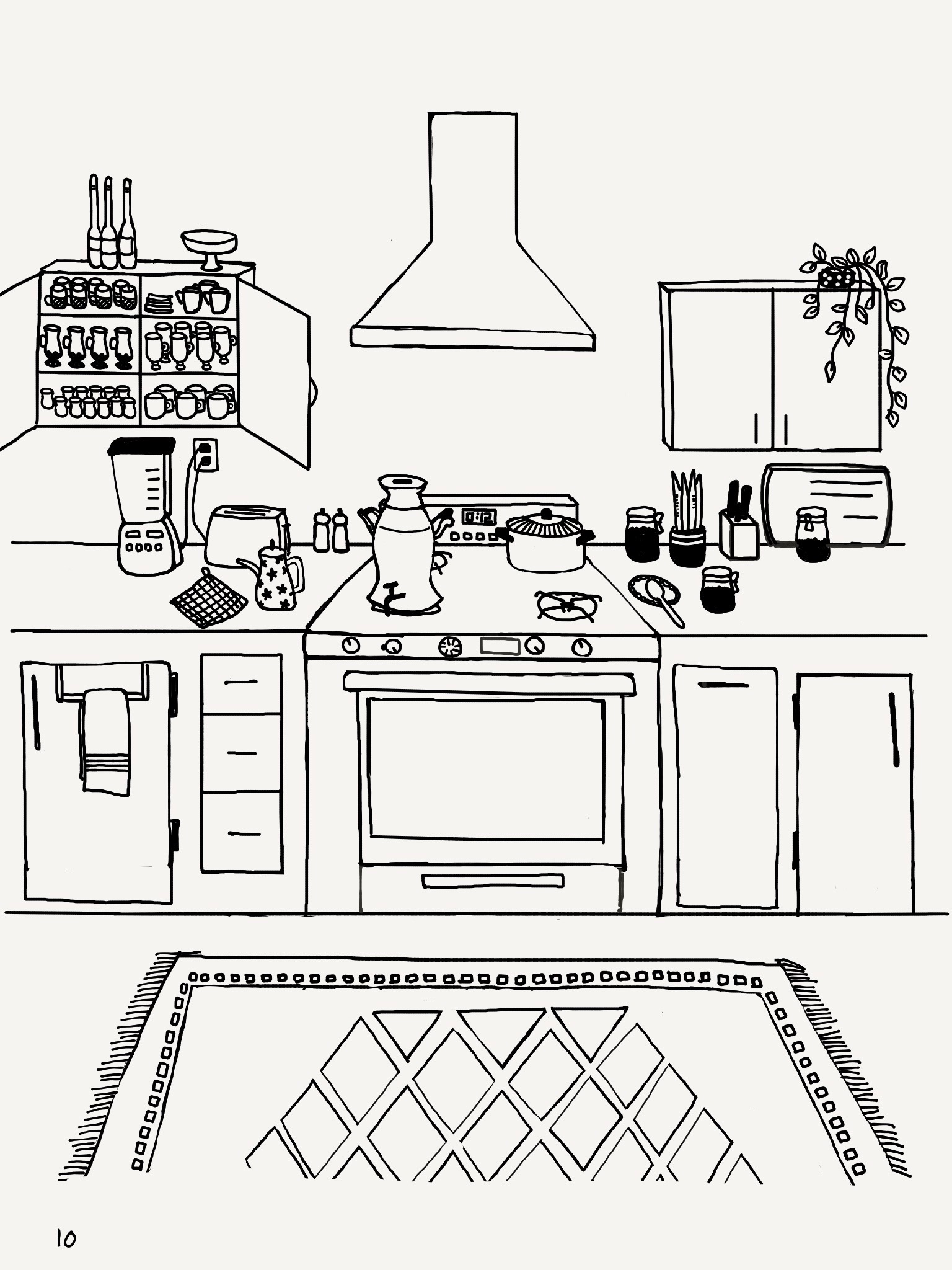

Of course, this is rooted in my own diasporic understandings of Iran. I understand that things change over time, a concept fundamental to the study of history, but I didn’t expect time to affect my concept of home. On my childhood visits to Iran, the country retained a timeless air for me. Long family lunches at a sofreh, followed by an afternoon nap. Family walks to Isfahan’s Zayandeh Rud, paired with boat rides and cotton candy. When you visit somewhere every few years for a few months at a time, it becomes a home. A home you don’t expect to shift under your feet. But as I grew older, I began to see the signs of Iran’s rapid social, economic, and cultural changes all around me. Lunches were now served at dining tables. And the Zayandeh Rud was dry.

So I did as one does – I began panic drawing. I drew what I could to preserve these fleeting memories for myself. I drew inspiration from the everyday, mundane scenes that I wanted to remember. After I returned to the U.S., I started to share the illustrations on my instagram page, @diasporaletters, where I include bilingual captions that reference both meaningful and inane conversations with my family about everyday life.

What began as me trying to document these different spaces for myself has turned into a larger project. A selection of these digital drawings were shown at my first solo-exhibit this past month at Twelve Gates Arts, a gallery that features social justice-oriented pieces in their Philadelphia space.

The exhibit featured prints of my drawings and a projected gif in a fragmented, nonlinear format, where I explored the interchangeability of each scene. No matter what order the pieces were in, nothing fundamentally changed. The takeaway – the poetry of repetitive scenes – remained the same. Some of the illustrations drew heavily from my personal memories, others inspired by photographs and other materials, and some drawn directly from within the space they depict. Each piece speaks to a larger story.

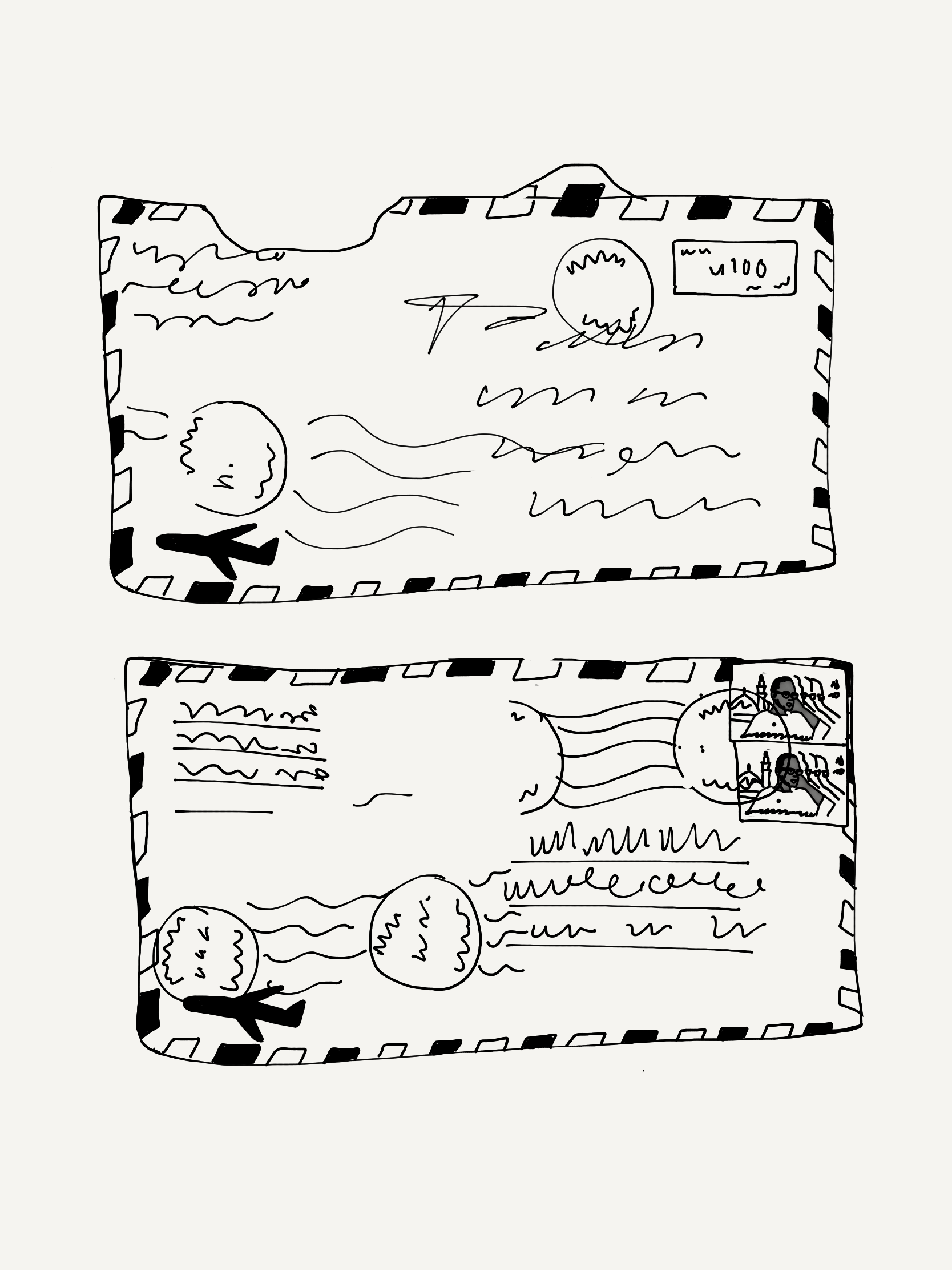

As a historian, I am drawn to finding the history behind these banal moments as well. As I reflected more on my work, I realized that I wanted to develop a project rooted in narrativized stories that are more than just individual, disjointed scenes from everyday life. I have been working with Shane Nassiri, an animator/filmmaker based in West Texas, to develop a documentary film based on the letters and packages sent back and forth between families based in Iran and diaspora in the twentieth century, using my graphic work as a starting point.

The film will include archival footage, found audio, interviews, and more, tracing how people negotiated distance and longing through tangible expressions of love and belonging. Our goal with the film is to illustrate and animate real stories about these connections.

We want the film to be bigger than us, and would love to encompass as many different relationships to diaspora as possible. We’re looking for stories that range from the banal to the spectacular – were you forced to write Nowruz cards to people you’d never met in Iran? Did you receive books or clothes in the mail? Did you hear about big life events – weddings, the birth of a new relative, deaths – via letters?

If you have a funny, scary, wholesome, sad, or otherwise interesting story that you would like to share with us, send me an email at beeta@diasporaletters.com.