Lucy Wallwork is a Masters Candidate in Urban Planning at the University of Manchester. Her recent research projects look at the dilemmas and challenges of urban policy and development in post-socialist countries. Ajam Media Collective’s ‘Məhəllə’ exhibition ran from June 8th to June 16th at the Artim Artspace in Baku.

‘Məhəllə’ – an exhibition at ARTIM gallery in Baku’s old city – brings the work of the ‘Mehelle project’ off the screen and into a three-dimensional space that captures the experience of wandering the streets of the recently demolished ‘Sovetski’ district, street names and all. Designed as an exploration of nostalgia, family histories, and the ‘social biography of things’, it is only minutes away from the gleaming towers, polished marble, and tourist cafes of the ‘new Baku’, but gives a taste of a disappearing world.

The exhibition (and project at large) is named after the concept of the məhəllə, or a traditional neighbourhood or quarter derived from the Arabic word mahallah. It was, and in some cases, still is the main social organizing unit for people in cities across the Middle East, Caucasus, and Central Asia. For hundreds of years people worked, celebrated births and weddings, buried their loved ones, resolved conflicts, and formed collective identities in these spaces. In Baku, these spaces of everyday life are still present, but they are slowly disappearing due to new visions of an ideal public space.

The Sovetski district was the quintessential məhəllə. Originally sheltering lower-income families who worked in Baku’s booming oil fields during the mid-19th century, Sovetski soon became a bustling neighbourhood, consisting of approximately 50,000 residents– a colourful cast of professors, taxi drivers, families, teachers and everything in between. With over 200 historic sites such as old courtyard homes, public baths, cafes, and places of worship, Sovetski served as the heart of “Old Baku.” In 2014, around 10,000 homes were destroyed on the site to make way for a new urban park, bringing an end to Sovetski’s tight-knit community and support network.

I have been following and researching how the inner city fabric of Baku has changed since the onset of the latest oil boom and was fascinated to explore this disappearing world. Anthropologist Bruce Grant once described the ‘hyperkenetically changing skyline’ of Baku as something of a ‘collective passion’ among Bakuvians – this exhibition gives us a chance to pause and reflect on what is being lost in Baku’s makeover. The very setting of the exhibition is meaningful – a gallery in a hidden corner of the UNESCO-heritage old city, which has seen its own share of ‘beautification’ treatment beginning in 2010.

On entering, you have the chance to explore the digital repository of sights and sounds that Ajam Media Collective’s project has been meticulously compiling over the years – giving 360 degree views of places you will now find flattened foundations and new four-lane highways.

However perhaps the most successful part of the exhibition is the installation piece that plays on the modern Bakuvian understanding of the ‘public realm’ – a gharish room filled with a lonely bench and digital fountain. Anyone who has sat in one of the city’s other new urban renewal projects, ‘Winter Park’, will recognise the experience.

The room is covered with pink marble vinyl and an upside down fountain, as it attempts to move between fantasy, reality, and kitsch. Fountains were originally functional, connected to springs providing drinking water, bathing, and washing for the residents, as well as public spaces for congregation and communication. In today’s Baku, however, fountains are a tool for beautification in city parks and squares.

Depending on who you speak to, Sovetski is alternately described as a ‘slum’ and ‘drug den’, or with emotional recollections of a vibrant, ‘human scale’ neighbourhood. There are plenty who point out that many Sovetski residents were happy to move out of the district to a shiny new high-rise block, and that question is a complex one, but what the fountain does is start a discussion about what we are replacing these demolished neighbourhoods with, and what ‘public space’ means in a ‘beautified’ city?

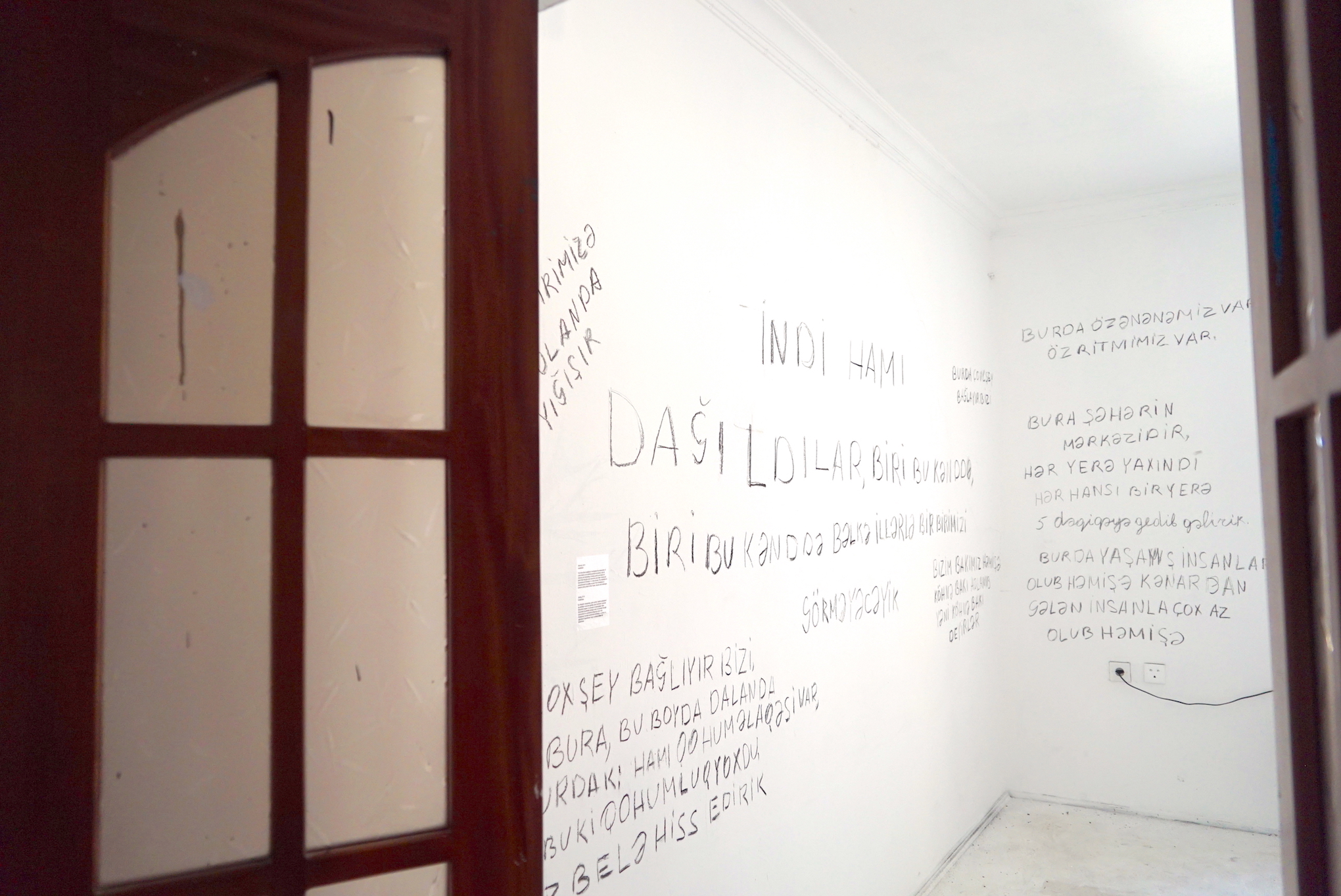

Upstairs an interactive installation investigates the intersection of urban spaces and archival practices and how they become sites of memory and witnessing. The installation invites guests and visitors to share their thoughts and memories about their homes and impressions of Sovietski in a video format. The installation is also complemented by words of Sovetski residents scrawled on the wall– as if their hopes, dreams, and challenges are struggling to be heard among the sound of bulldozers and jackhammers.

– “When something happened to anyone of us, we would all gather together. Now they’ve torn us apart, some people are in one village, some in another, it may be years before we see each other again.”

– “It feels like, even in this small alley, we’re all family, even though we’re not related to each other.”

– “For me citizenship starts at home, the first thing I should protect is my home, after that my street, after that neighbour’s house. A citizen starts at home, and that’s why I won’t give mine up.”

– My best and my worst days passed in that house. My grandmother passed away there, my uncle and my aunt.”

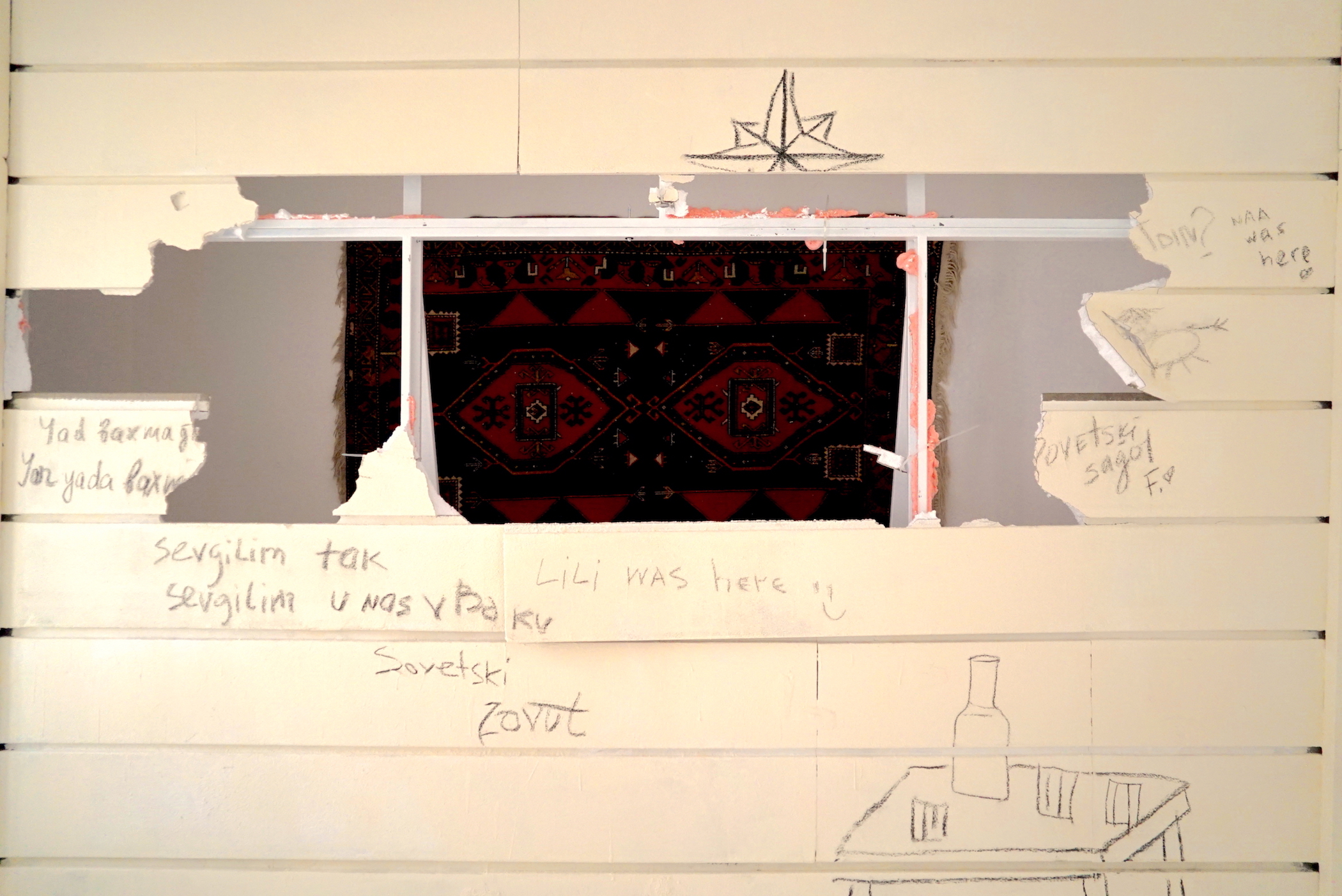

The “façade” room is a powerful installation made from styrofoam, replicating the superficiality of contemporary beautification initiatives. The installation is inspired by the wall façade on Nariman Narimanov street that will soon obfuscate the dilapidated houses when the park opens. On opening night of the exhibition, the styrofoam material (which has been used in a number of instances in Baku for beautification purposes) was covered in graffiti by viewers before being torn down and revealing a traditional portrait carpet representing daily lives of the people still inhabiting these houses. It serves as a strong condemnation of the Potemkin village-like façade urbanism’ that excludes anyone who does not fit with the image of this ‘new Baku’. The work explores notions of illusion and disillusion, visibility and invisibility.

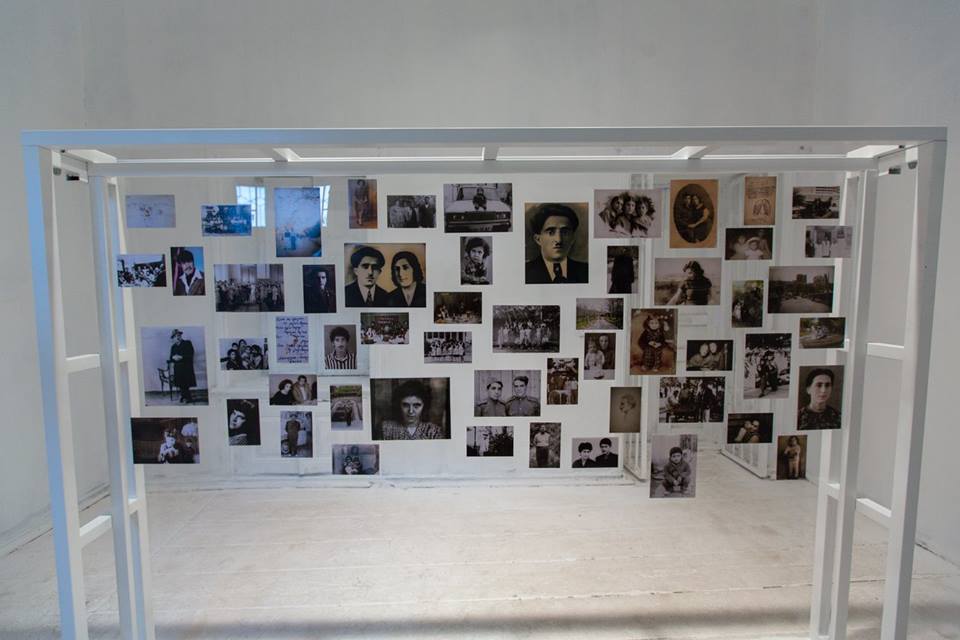

In another room, a collection of photographs grasped from the ruins bring to mind not an orderly evacuation but the kind of precious family memories abandoned by refugees fleeing warfare – the loss of hope evoked by the family photographs makes this the most sombre part of the exhibition.

When residents rushed to move out of their homes after the announcement of demolitions, many left behind things that are connected to social life of the neighbourhood such as photo albums, old books, video cassettes, drawings, letters, postcards, diplomas, shoes, and plates. Using photographs donated by Sovetski residents as well as those excavated from destroyed homes, the installation explores how certain material objects are embedded in cultural memory, and how future generations have now lost an important source of family history.

The exhibition gives the sense of a photograph captured mid-fall, with the walls often falling down around the edges of the image. However the exhibits steers clear of the danger of a sickly nostalgia over a lost world of ‘pure’ tradition and eastern exotica. As is the case in many neighbourhoods targeted for “revitalization,” many Sovetski residents were ambivalent about leaving their homes. Some welcomed the financial compensation and promises of a new start in newer apartment complexes, while also regretting the loss of their familiar streets and social ties. The ‘Məhəllə’ successfully attempts to capture these differing, yet not entirely contradictory sentiments.

In another room entitled “Sovetski Stories,” the exhibition shows a number of short documentaries portraying the human and non-human inhabitants of Sovetski. Composed of resident interviews collected from 2015 to 2018, the work alludes to the dense social fabric of the neighbourhood with TVs scattered across the room, reproducing the cacophony of everyday life in Sovetski.

One of the rolling videos shows a wedding the curators stumbled across, witnessing a Hummer awaiting the bride in the narrow back streets of the Sovetsky district, adorned with kitsch pink chiffon and gaudy cushion lettering… this was Sovetski, not a neighbourhood stuck in time but one which had its own urban rhythms cut short.