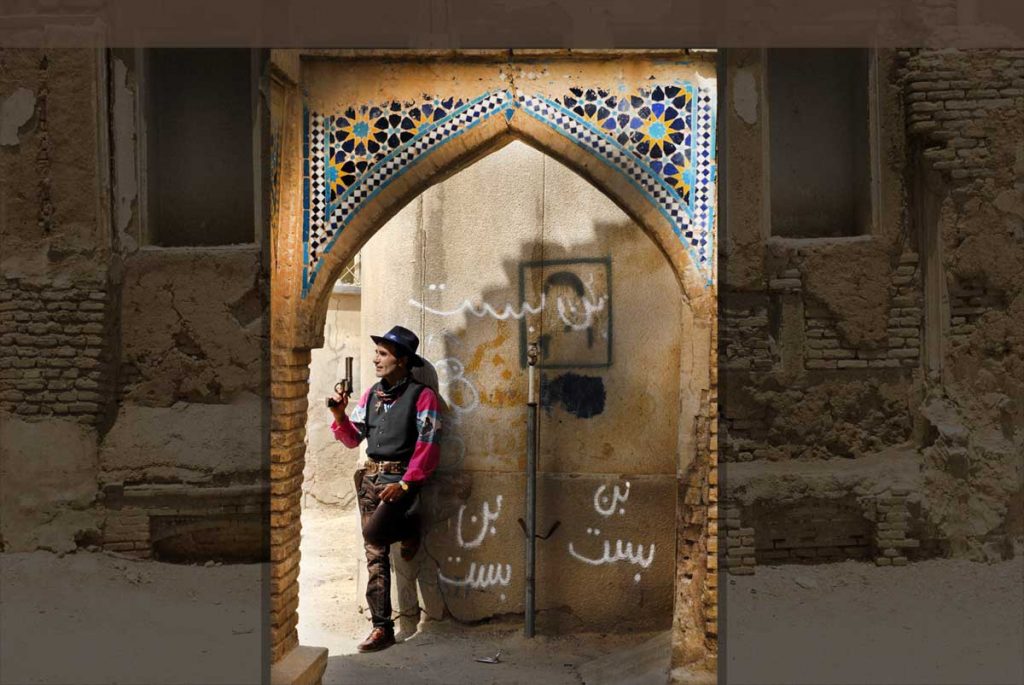

As the camera opens to reveal a cowboy’s stubbled face and ink-well eyes, the audience at once recognizes a familiar figure. This recognition is troubled by the cowboy’s lilting Persian, but the appearance of an Iranian cowboy is rare enough to force you to suspend disbelief. There are many ways to tell a cowboy’s story, as those familiar with John Wayne, Sam Peckinpah, and late-era Mansour know well. But in My Name is Negahdar Jamali and I Make Westerns, director Kamran Heidari chooses an unusual genre to depict his Iranian cowboy: a Western documentary. In his humanizing portrait of a Shirazi cowboy-cum-director, Heidari successfully weaves the bizarre, the unexpected, and the hilarious to tell a tale of an Iranian cowboy masculinity and the unexpected world it inhabits.

The documentary film follows the title character as he writes, directs, and stars in his own Western films. Negahdar travels around his hometown of Shiraz as he tries to make one last Western. The plot is straightforward but the storytelling isn’t, as we go back and forth between Kamran’s camera and Negahdar’s Hi-8. The audience sees Negahdar explain his love for the Western genre interspersed with tracking shots of him walking through Shiraz cadging friends into acting for him, buying props and costumes for the movie, and dealing with everyday life. We also see plenty of the “making of” of this movie, with Kamran, in his role directing a documentary, appearing on screen discussing how to shoot and in one memorable scene, playing with Negahdar’s son. We also see bits and pieces of Negahdar’s final movie and some of his previous ones in the course of the story.

If this sounds a bit confusing, truth be told it is. But it is all intentional, and can best be understood as a bilingual movie. We go from the visual vocabulary of Westerns to that of documentaries and back again while trying to figure out the difference between Negahdar’s fantasy movie world and his real world in Shiraz. Sometimes it’s easy: when he’s working as a laborer cleaning trucks and when his wife is concerned about family finances. Other times, when he’s discussing the Western masculine ideal, it is a bit more convoluted. This “Western masculine ideal” is the crux of the film. There is a tremendous difference between the “West” of Western films and the “West” as a theoretical space that features in the world of ideology. The West imagined by Negahdar Jamali is not the West imagined by Iranian intellectual Jalal al-e Ahmad. This isn’t a West of capital, industry, and dehumanization. The “West” of Westerns is a lawless, wild (and fictitious) place created in rejection of 20th century society. While Al-e Ahmad looked to socialist Israeli Kibbutzniks to combat the toxicity of modern life, Jamali looks to cowboys. Bringing the Western to his hometown, Jamali uses the vocabulary of Westerns, the hats and six-shooters, to talk about issues he finds pressing back in Shiraz. He follows the proud tradition of the Italian Spaghetti Western, using the cinematic trope to discuss life at home.The Western is a film genre that takes an 1800’s setting where “civilization” comes to a lawless community, setting up a conflict that usually ends in a gunfight.

The Spaghetti Western is originally an Italian adaptation of the mid-century American genre. Directors fell in love with Westerns’ discussion of solitary individuals in the countryside, using the trope as a way to critique the country’s rapid post-WWII urbanization. The original Western is 1924’s The Virginian, in which the protagonist attempts to form law and order out of the chaos around him. Austin J. Fisher, a lecturer in Media Arts, argues that the film was a “polemical lament at the passing of the Old West [that] commented more on fin de siècle social ills than on Frontier history.”

Westerns use the past to comment on society’s present, but the 19th-century world they portray is often patriarchal, with casts consisting nearly entirely of swaggering males. From The Virginian to the mid-century white-hat Westerns to the morally complex Spaghetti Westerns, the genre uses the 19th-century American West to describe contemporary masculinity. My Name is Negahdar Jamali is no different.

In the movies he films, Negahdar uses the vocabulary of Westerns to discuss the issues he finds pressing back in Shiraz. Underemployment, marital strife, and Afghan refugees all feature in this film. Negahdar uses this vocabulary to make common cause with his audience. In his explanation of the role of the Western in the United States, Roger Ebert wrote that “in hard times, Americans have often turned to the Western to reset their compasses. In very hard times, it takes a very good Western” to make the audience empathize with the characters and associate themselves with the protagonist’s struggle. In an in-depth essay that plumbs the depths of Ebert’s quote, Dylan Hintz writes that:

“This statement provides the idea that Westerns work as morality stories, and help to establish a prototype for a man to base his idea of masculinity, the ideas of what a man is accountable for, what his responsibilities as being a man are, and what he must do in terms of violence to protect those weaker than him, off of in times of moral dilemma.”

The Western’s role as a masculinity/morality tale has survived – and even thrived – in the genre’s exportation beyond American shores. Throughout Kamran’s film, Negahdar is constructed as a conflicted man. His marriage is in shambles, his son picks on him and abuses him, and he is making barely enough money to survive. All that said, he has friends, a hobby he loves, and a dream to make movies. Negahdar embodies a negotiated existence: in his movies where he is the star, however, he lives a bold life of suspense and swashbuckling, a romantic and dashing lead in the story that exists in his camera’s Shiraz. This is no different from the audience’s complicated life, just perhaps more dramatic. The viewer of Kamran’s film sees both Negahdar’s heroic image of himself and his reality. However, the way Kamran’s film is shot and edited, one is always aware that the documentary My Name is Negahdar Jamali and I Make Westerns is of the “experience of truth.” The documentary genre is never entirely honest, and the filmmaker (in this case Kamran Heidari) can selectively set up shots and edit the film to portray the story in his preferred way. In My Name is Negahdar Jamali, the audience is always aware that Kamran is portraying Negahdar in a way as staged as Negahdar portrays himself in his own films.

This duality creates the bilingual aspect referred to earlier. The audience is viewing the same of a man trying to make sense of his place in his community twice: first in the movie Negahdar is making and second in the documentary Kamran is making. There’s friction between the two cinemagraphic languages, and Kamran milks the friction for humor quite well throughout the film. When Negahdar buys drapes to cloak his “Indians” in, it’s impossible to see them as anything but drapes for the rest of the film. But once your eyes adjust to this – and it takes a bit of adjusting – the “bilingualism” of the film gives the characters and especially the city an added depth for the audience to view them through..

The streets of Shiraz and the hills outside of them are constants, and it stands to note that Kamran’s company is named “Shiraz Film Group” and that one of his stated professional goals is to bring the stories of Shiraz out to the rest of Iran and the world. In many ways, his films are about the people and the city, no different than the photographers who make up Humans of Shiraz. Kamran’s story in My Name is Negahdar Jamali is unique, and Kamran uses it to give his hometown a greater presence in the Tehran-dominated Iranian cinema scene. Negahdar Jamali is the star, but in both films, Shiraz is the strongest supporting actor.

When an audience sits down for a film, they build their preconceptions from the genre promised and the cinema’s context. I entered the theater expecting a Western, a documentary, or a “quirky” fish-out-of-water tale. I was surprised when I got all three; not a compromised take on each genre, but a film that uses each genre to tell a whole story about a man, a place, and the man’s place in that place. Understanding the Western genre is vital to understanding Negahdar’s worldview that Kamran is trying to explain through his own documentary. And as peculiar as an American audience may find a working-class Iranian man who makes his own Westerns, nobody in the film (save for perhaps Negahdar’s wife) finds it strange at all.

My Name is Negahdar Jamali and I Make Westerns is far more lighthearted than most International Film Festival fare. Like Facing Mirrors, the tale of a transman named Eddy negotiating life in modern Tehran, My Name is Negahdar Jamali discusses the roles of identity and society within Iran. The sense of place, and a man’s negotiation of that place, is peculiar to the Western genre. By imbuing the genre with a particular Iranian-ness, in location, in language, and in identity, a fresh, strange, and altogether wonderful vision of this particular Iranian comes through. It changes the genre as well as the popular image of Iran, using the Western to erase a false East/West divide. The man with a square jaw and jet-black eyes is no stranger but a familiar face thanks to years of the genre’s conditioning. In My Name is Negahdar Jamali, though, Kamran Heidari has given the audience a wholly new way of looking at him.

All images are property of Shiraz Film Group unless otherwise noted.

1 comment