The following is an interview with Giorgi Rodionov and Nino-Ana Samkharadze, members of the Tbilisi-based photography cooperative, the 90x collective. Ajam editor Rustin Zarkar spoke with the collective about the publication of “My Parents Don’t Talk to Me,” a photography book composed of old photographs found in Rodionov’s family home that offers an intimate glimpse of family life in Soviet Georgia.

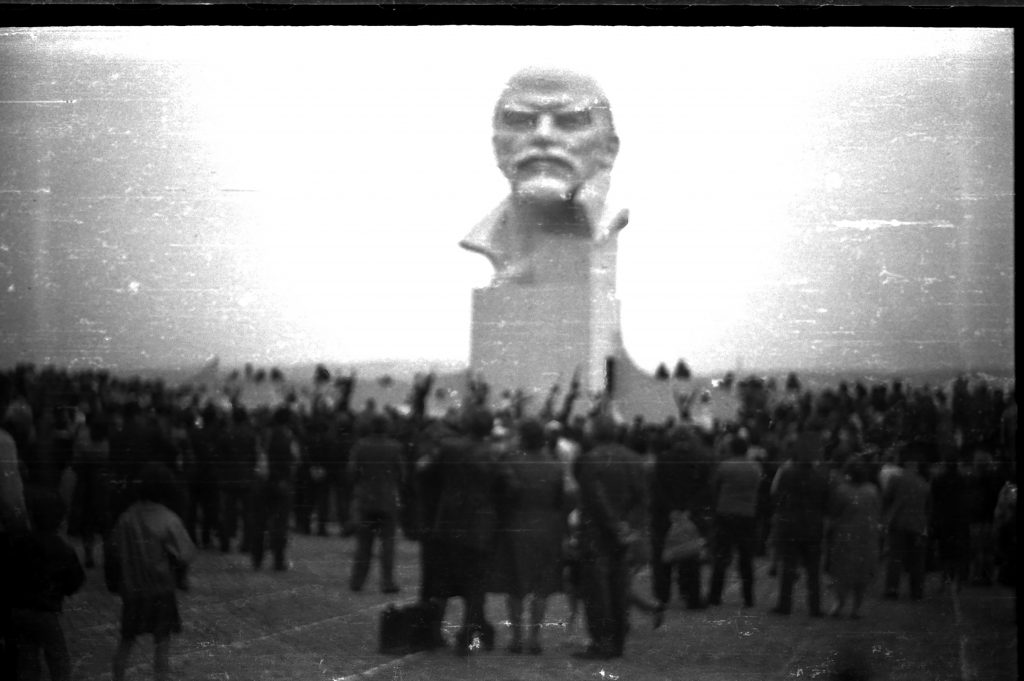

The 90x collective takes its name from the decade in which its members were born and raised: the 1990s, This period, which opened with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, was marked by rising nationalism, secessionist movements, traumatic civil wars, and major economic insecurity for Georgians and many other people across the newly independent states. The hardships not only shaped the collective identity of those born in the 1990s, but also challenged the material security and worldview of older generations, whose skills and experiences in navigating the former Soviet system were no longer viable.

As the Soviet experience has become an ever more distant memory, the children of the 90s, their parents, and grandparents must reckon with its legacy and find avenues to share personal stories across the generational divide, especially since many older Georgians choose to remain silent. It is within this context that Rodionov published “My Parents Don’t Talk to Me,” which is meant to spark a conversation between different generations of Georgians coming to terms with the history of Soviet Union.

Ajam: Your book is a collection of photographs that span the second half of the twentieth century– from the late Stalinist period of the early 1950s to the beginning of perestroika in the mid 1980s. How and where did you find these photographs?

GR: I found the photographs during my year of military service. I was an avid photographer when I was younger, and one day I returned to my parents’ home in search of my old works. I couldn’t remember where I placed them and I wasn’t sure if they had been moved, so I began to look in parts of the house that are not frequently used. It was in one of these rooms that I found an old box, inside of which were hundreds of dusty photographs.

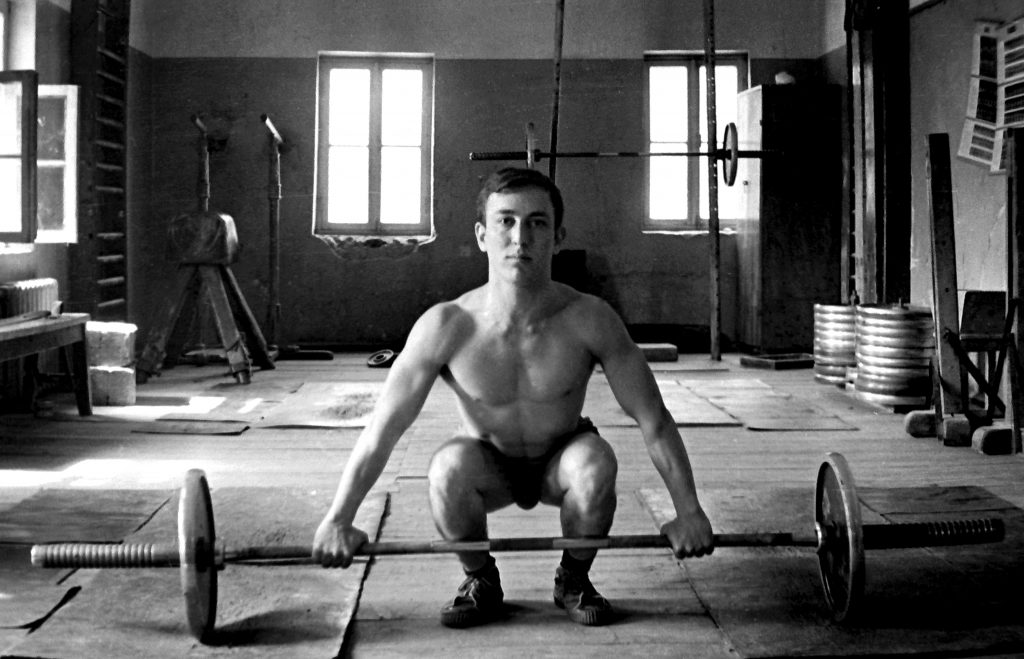

I was curious to see what they were of, so I cleaned and scanned them. There were around 600 of them, dating from the 1950s till the 1980s, and I was able to recognize many places and people in them. However, I was surprised that I knew nothing about the stories being told in the photographs– nobody had ever shared them with me. I started to think more deeply about why my parents don’t share any of their memories from this time, and then I realized that it just wasn’t my parents; it is an entire generation of Georgians who choose to stay silent about their past.

Ajam: It is clear this frustrated you, and it seems you are alluding to this intergenerational silence with the title of the book. Did you actually confront your parents about this silence once you discovered the photographs?

GR: I definitely tried to open up a conversation. One night I approached my father with one of the pictures in hand. It was a photograph that he had taken of himself. I asked him, “Hey that’s you, right?” and he just responded, “Nope, that’s not me.”

I was so confused; it was clearly him in the photograph! This was just one instance, but it happened several times. I was upset at first, but then I started to wonder why my parents don’t have this ability to share their stories from this period. Was it due to a past trauma or was there some political dimensions to answering the question?

In Georgia, it is a bit controversial to say something pleasant about the past, particularly regarding the Stalinist period. Sometimes just saying that you had a good life during those decades can be construed as tacit support for the regime.

Ajam: This is not unique to Georgia. I’ve seen this sort of hesitancy in Russia, Azerbaijan, or Armenia– talking about nice things from the past is often labelled as misplaced nostalgia or even apologia. Considering the mass repression and executions that occurred in the Stalinist period, I understand the inability to share more positive stories of one’s youth. Do you think it is because people don’t want to be labelled as complicit?

GR: Yes I think that’s definitely part of it. Often times people seem to remember an “official history” or focus on political issues when they attempt to narrate the past, and of course that is all wrapped up in our current debates about the Soviet legacy and Georgian-Russian relations.

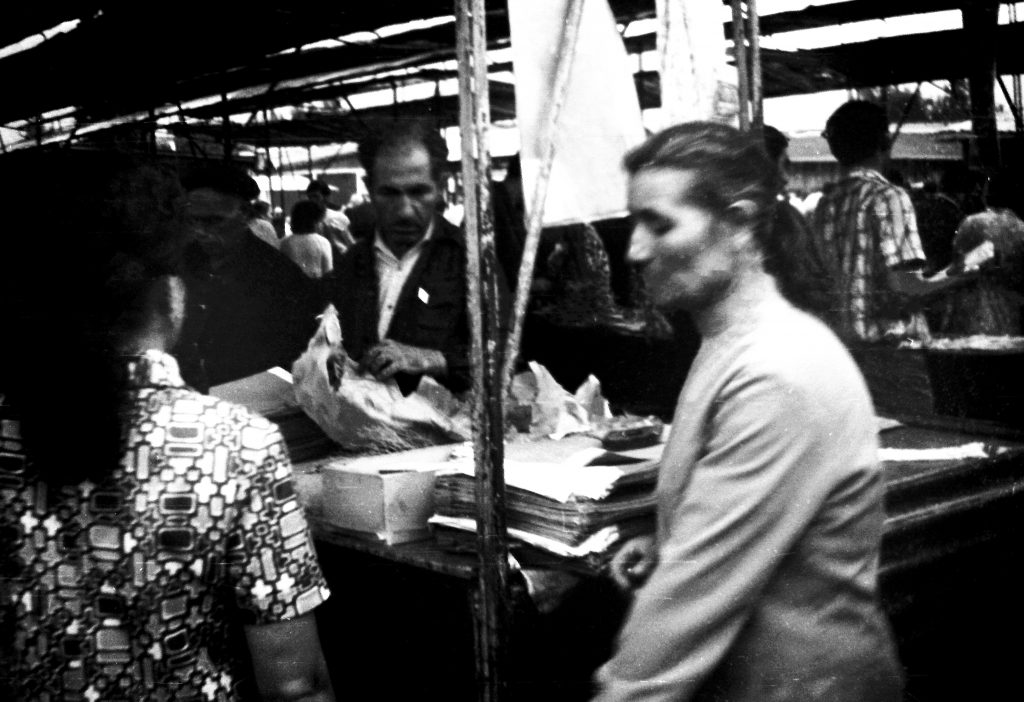

But I wasn’t really interested in that; my parents were once young and in love, they used to eat ice cream– why shouldn’t they remember and speak about this! What did the bread look like, for instance? It’s such a banal question, but my generation has no clue. I’m not asking them to give an opinion on all the political dramas from back then, I want to know about their daily lives.

Ajam: In ethnographic interviews, people are often hesitant to open up about their lives, especially if you directly ask them. But in the case of our work in Baku for example, we have been more successful by using an object to direct the conversations, whether they be a building, map, or a photograph. The interviewees tend to be more comfortable speaking from a position of authority on an object or idea rather than talking about themselves. In your case, however, the photograph didn’t seem to help as a tool for communication.

GR: No, the photographs didn’t help at all. My parents never opened up. That said, I was able to discover stories by looking carefully at each picture. They reveal a lot about the person who took the photograph so long ago– who they were friends with, what they ate, where they went on holiday. One of the things I find most interesting about this project is how there is not just one photographer, but instead many individuals who used the camera.

Ajam: It’s something we do not think about much, especially in the age of smartphones. Nowadays we see the camera as an extension of ourselves, with each of us capturing and curating our own personal photographs. But just twenty years ago cameras were much more communal as objects. They would change hands often.

GR: Yes, the camera has its own character.

Ajam: How did you print and publish the photographs?

GR: I decided to print them on a semi-transparent paper that is used to protect old pictures between album pages. I vividly remember that feeling as I was flipping through those dusty dirty sheets, so I wanted to use that same exact material. The transparency of the paper means you can see multiple photographs overlapping at once. It reminds me of how memory works— memories are sometimes layered and they can blend; they become more diluted and uncertain as time goes on.

Ajam: How did select the photographs for the book? What sorts of features were you looking for?

GR: As I mentioned earlier, I found a total of 600 individual photographs, so you understand how it would be difficult to curate them. I decided to make editions of the book which are composed of different sets of photographs. I did not just want to focus on one set of stories. Each edition gives a different feeling and works around a particular theme.

For example, the book that I showed you plays with the idea of innocence and hardness. This edition starts with idyllic images of landscapes and city life– mountains, birds, and beautiful buildings. However, as you reach the end of the book you start to see more unsavory elements. The last set of photos depict three people who I don’t recognize who are posing with a pornographic magazine (who would do that?!). There’s also some photos of demolished and ruined buildings at the end. The book grows moves away from peacefulness and grows into something more disturbing as it progresses.

Ajam: Have you shown your parents this book? What was their reaction?

GR: I can’t really say if they liked it or not. The only reaction I got from them was: “Yea, we don’t talk to you, fine!” I told them that this book was about starting a conversation about their past lives, but unfortunately that did not go anywhere.

However, I found different reactions from other older Georgians who have seen this book. Sometimes they recognize the problem of silence and, as a consolation, they attempt to share some memories. But almost always the conversation turns to some political history as opposed to a discussion of their biography. Other times I receive some disparaging comments– people often complain that my generation just want to bring up memories of hardship for no reason!

Ajam: Considering these reactions I totally understand why the concept of generational divide is important to the 90x collective. How does this project fit into the larger project?

NS: Every generation has a particular set of circumstances that shape their experiences and collective identity; our generation was shaped by the transition and the problems that arose from it, such as nationalism, war, and displacement. We realized that it was important to come together and address some of these lingering issues that are very close to us.

We are photographers who have been shooting together for ten years, and we realized that we could give some insight to people who are not familiar with some of the things we have experienced. In this way, photography is a perfect medium for us.

For example, Lash Fox Tsertsvadze is part of the LGBT community, which is under pressure from religious and socially conservative forces here in Georgia. Some of his projects have highlighted queer sensuality, and in fact he was one first queer photographers to be showcased in Georgia.

Mano Svanidze latest project focuses on ghosting, a painful but common dating strategy that many of our generation across the world have experienced. She’s also explored how Georgian youth have struggled to carve out their own private spaces in a communal and family-oriented society.

Thoma Sukhashvili is an IDP from Ossetia, which has been occupied by Russia since the 2008 war. A lot of his work explores childhood, Georgian language politics and the status of the Ossetian language, and conflict zones in the region at large.

One of my latest projects also featured the Ossetian conflict zone. I photographed the children of Tserovani, a new village constructed after 2008 to house 8,000 internally displaced people.

Ajam: Your individual projects attest to your diverse lived experience and interests. Why do you think “generation” is a useful lens from which to view these works? It is clear that people of a generation do not make a homogeneous group.

SN: I agree, but I do think that “generation” has some validity in the context of Georgia and many former Soviet states more so than in other places. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, things came crashing down for our parents and grandparents. Our parent’s generation is called the lost generation; they were too old to adjust to new economic and political realities, and a bit too young to take advantage of the social services for the elderly.

Our generation, which grew up in this period of transition, is better positioned to deal with these changes, but we have witnessed our fair share of instability. Our parents want us to be successful but are reserved about our experiments.

But really, I do feel that there is something special— when we discuss among ourselves, we know! It’s not just toys and TV shows. It is even in the wider region— when we meet Azerbaijanis and Armenians, we all know! This collective is all about sharing personal stories that reach wider topics.

What is the common theme in our works? They have no similar lines in terms of photography, but that’s totally fine because the main goal is to convey our experiences to the audience and see how they feel. Giorgi’s work is a starter pack for our whole collective, and now we are trying to find ourselves through this whole blurry thing.