The following interview is with Leyli Gafarova, an independent filmmaker and the co-creator of Salaam Cinema, a community-driven independent cinema space showcasing non-commercial, locally-made, and historical films in Baku, Azerbaijan’s capital. Named after Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s 1995 movie of the same name, Baku’s Salaam Cinema is a venue for the performing arts and offers a wide program of exhibitions and educational workshops.

Following their opening in January 2019, Salaam Cinema moved into their current venue, a historic Molokan prayer house in the heart of Baku. Molokan is a term describing Eastern Christian groups that developed in Slavic lands but rejected central Orthodox rites. In the 1830s, the Russian Empire forcibly transferred many Molokans to the periphery of the empire, and a group was settled in Azerbaijan. In 1913, an architect of Molokan origin built the prayer house with the aim of gathering the dispersed Molokan populations across Azerbaijan.

Following the Bolshevik Revolution, the prayer house was converted into a radio broadcasting building in 1926. The home of the radio show, Danışır Bakı (Baku on the air), the building became a bastion of the Azerbaijani language and an everyday fixture of Baku cultural life. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the building was privatized and then rented out as office space, but it had fallen into disrepair.

Salaam Cinema, with the help of the community, refurbished the building and once again transformed it into a cultural landmark. However, as of March 2019, the landlords have moved forward with plans to demolish the historic building, fitting with the general trend of gentrification and property speculation that has driven Baku’s rapid urban development since the early 2010s. Salaam Cinema, however, has resisted the demolition efforts, and has galvanized its supporters to not only save a prominent independent intellectual space in the city, but also a valuable piece of Baku’s urban and architectural landscape.

1) How did Salaam Cinema start? What are the goals of the project and why is it so important to have such space for movies and cinematic history to be community-driven and in Baku?

LG) Three years ago I returned to Baku after living in the Netherlands, and I saw that there is no place for alternative cinema. There were still some old movie theaters that dated back to the Soviet period, but one by one they were being demolished. We had the idea of giving these architectural forms back their original function. Right in the heart of the city we found a film theater called Vatan, meaning homeland. It was an amazing place with a large salon that was being used as a chai khana (tea house) and for people to play billiards and ping pong. There was even a darzi (tailor shop)! There was also a small salon where for three manat ($1.75) you could go and watch a movie. It had an old projector and a bunch of historical films that the owner had collected over the year. Many couples used this place to get intimate. We loved how organically a community was formed in this old cinema so we just wanted to give back what was missing.

Two years ago, we returned to the space to speak with the owner about our plan for a screening, but the building was gone. Sometime in the middle of the night, it was demolished– even the owner himself couldn’t stop it. It was a very strange story and till this day no one quite knows what happened. Either way, it was too late.

My partner Ilkin and I began working on different projects and last year we started to think about restarting the project. We looked for a new space and we found this wonderful old Molokan prayer house that was abandoned and in a poor condition. Somehow, we were able to enter the building by talking to the security, and they agreed to rent it out. For one and a half months we did renovations ourselves, and that is when the community-building started. People started to come with paint and brushes in hand. Our friends, friends of our friends, and people that we have never seen in our life came and pitched in. We immediately understood that this is not just going to be a cinema, it is going to be something more.

2) What sort of films did you showcase?

LG) Our main goal is not to show commercial films since those are already dominating the cinema screens in the city and Azerbaijan at large. We want to support local filmmaking and the history of that tradition here in Baku. With that in mind, we have screened many silent films from the 1920s and 30s that were produced in Azerbaijan. We invite young musicians and artists to provide live musical accompaniment to them.

These films are incredibly important because you can see how Baku used to be back in the day. You can recognize the streets and even see familiar events. For example, in the movie Bismallah (1926), you can see the Muharram processions that we’re actually happening that year. That sort of thing is important to share for our generation because we don’t know where else they could see that.

3) You mention 1926— this is right at the heart of the Soviet anti-religion and anti-veiling campaigns

LG) Exactly, and those movies and their themes are still important for us today. When we screen the film, we see how many of these issues have yet to be resolved in our society— especially women’s and gender issues.

In addition to older films, we support young filmmakers and screen their movies followed by discussions. Foreign movies and classics are also featured— basically anything our generation has not been able to see on the big screen. Moreover, we want to propagate gender balance by amplifying women and LGBT filmmakers. Really anything that contradicts what already exists in Baku.

As you know, cinemas in Baku are commercial. Whenever there is an independent movie made in Azerbaijan, it only gets about one day of screening because they usually don’t have the money to remain in the cinema and often they don’t advertise it in the right way. At some point, all local independent cinema ends up in the director’s shelves and not many people have the chance to see it. We try to find and invite these directors ans screen their films at our space. They often say that they never thought that anybody would want to see their films here in Azerbaijan, but apparently there is a community here that is interested!

4) In terms of historical films, how are you getting these films? Are you going to local archives?

LG) Luckily I have become friends with someone who works in the National Archives and each time I go there, he helps me find something unique. Unfortunately, I’m not very happy with the quality of the digitization of the movies. Some of them that have been done quite well, but there are some movies where the texts and images has been cropped out. We wish that there would be more attention to the preservation of these materials.

This weekend we are showing the film, İsmət (1934), a Soviet Azerbaijani film which tells the story of the first Turkic female pilot.

5) One of the major draws about Salaam Cinema is the space. As you mentioned, this was a former Molokan prayer house. Who are the Molokans and how does their history fit into the fabric of Baku?

LG) Molokans are considered a minority group in Azerbaijan. They were originally ethnic Russians that did not accept the practices of the Orthodox Church, and some don’t use icons or churches. They had t flee Russia because they were not free to practice their religion there. They came to Baku and in the 20th century they were able to build a house in the center of the city where they could unite. In 1913 they constructed this building and it served as a gathering point for all the Molokans in Azerbaijan.

But very shortly afterwards, the Bolshevik Revolution happened and as we know, they did not approve of religious practices. Luckily, they did not demolish the building and instead it became a radio station. When we came here, we found much of of the equipment and materials that belonged to the radio station. Even the ground floor was kept in the style of the original reception hall of the Soviet Radio Station, but this was demolished by the landlord in March.

6) Baku is going through this tremendous urban development project. A lot of old and historical buildings are being demolished to make way for high-density housing and luxury condos, but also public parks and new transportation infrastructure. As you mentioned, in the last couple of days the landowner has contacted you and said that you must vacate this building.

LG) Yes, when we came here in January 2019 we knew that the building was scheduled to be destroyed. We couldn’t even get a normal contract because of that, but we were ready to take that risk because we knew that if we were able to go inside, there was a chance that we could save the building. We didn’t know what the exact dates were. As is common in Baku, so many buildings are planned to be demolished but you never know when; sometimes it can take ten years, in other cases it can be less than one month. We thought that if make the building visible and attract people to it, we could save the building.

As I mentioned, we have been holding talks, screenings, and exhibitions after we renovated the building. We planned to make the downstairs area a chai khana, but just right after Novruz, we left the city to work on a project and when we returned we saw that the ground floor was completely destroyed. No one is taking the responsibility and everyone is blaming each other.

And just as we have been getting more support, the landlord’s super contacted us and said that we must leave. That’s when we started this campaign to make the building a historical heritage site. Now our fate is very unclear, the owner told us that we have to get out by May 5th, but if we leave, we know that the building will be demolished– so we are staying put! We have no idea what is in store for us.

8) So what are your strategies for saving the building?

LG) From the moment the situation escalated, we have never left the building alone. Every night someone is staying here to prevent something from happening. Often times they conduct demolition work overnight to make the building unsafe or unusable as a pretense to carry out the rest of the destruction. We have also written letters and petitions to the municipality and the heritage board to get the building registered as a heritage site, but of course this is a process that takes long time.

We are informing our community and are starting an online campaign. Different organizations have been approaching us to offer their help, but all of this has happened just over the last two days. Just yesterday, the superintendent came here and was about to cut off the electricity and tried destroy the stairs where we were standing. Tomorrow we have a EU-sponsored festival in which several embassies are involved, so I called the organizer of the event and told him that he needs to come right now or they’ll lose their venue! Right at the moment that they were about to destroy the stairs, the organizer came with the paper of the festival and was able to convince them to postpone the demolition till May 5th.

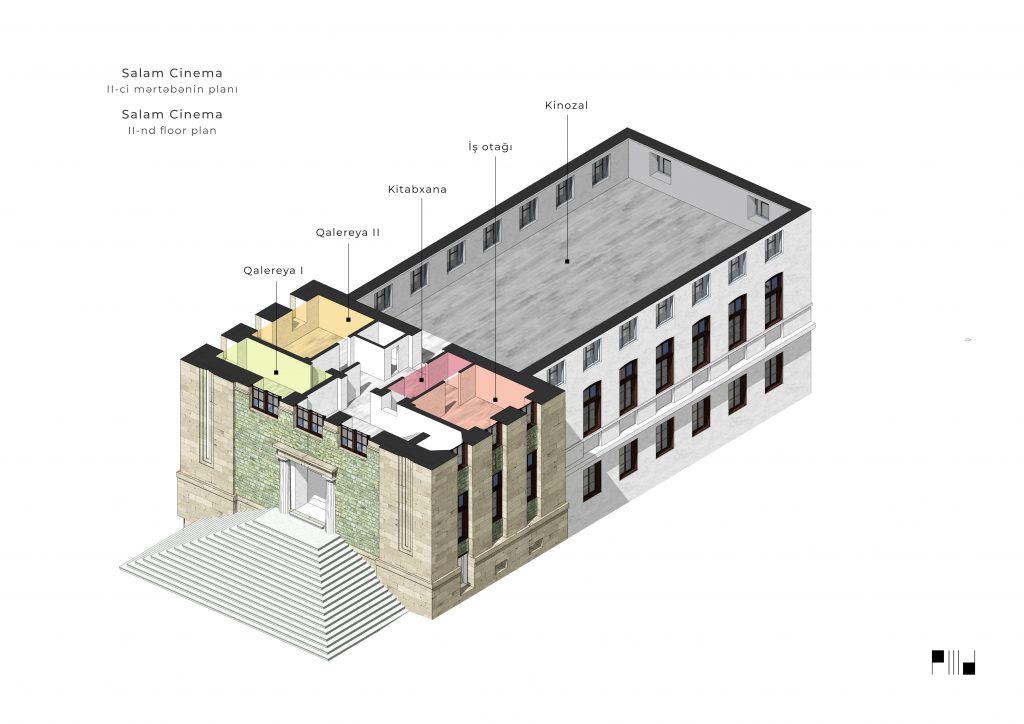

9) It’s amazing that the festival was able to save the building till the day after, but as you mentioned after tomorrow the the fate of this space will be uncertain again. We’re in similar circles online, and I have seen so much outpouring of support. You’ve done a really amazing job of raising awareness about this building and its demolition. For example, BBC Azerbaijan has an article that came out on Saturday and PILLƏ—an amazing Baku architecture and urbanism collective—has done research on the building and written an extensive Facebook post. What would you want people to think about or know about the space in case the building no longer exists in the future?

LG) In my reality, it is not possible that the building won’t exist. I really believe that we are able to prevent this demolition. The only thing I can ask is to be there with us and we will see what happens! But we will not get out that easily!

***

As of May 6th, after a confrontation with the landlord and demolition team, the building still stands. Salaam Cinema and their supporters are currently occupying the building. To learn more about their campaign, follow them on Facebook and Instagram.

5 comments