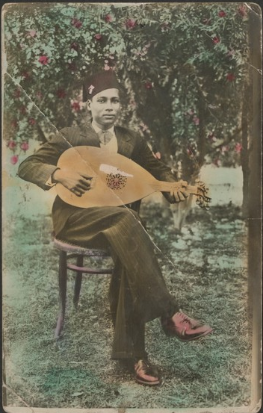

From Greece to Iran and North Africa to the Caucasus, the oud is played by musicians in many countries across the region as “traditional” or “folk” music. A large part of the world today considers this instrument part of their cultural heritage.

While globalization means that the oud is now sold all over the world, the oud has a fascinating built-in cosmopolitanism that stretches back much longer. On this mixtape, listeners can hear how the oud can serve as a vehicle for many performance styles including the Persian dastgah system, the Iraqi maqam, Armenian folk music, Turkish classical sanat music, and Greek folk music.

The oud is a short-neck and fretless stringed instrument traditionally made of wood. For the uninitiated, imagine a cross-between a mandolin and a guitar, minus the frets. The lack of frets renders the oud a versatile instrument, as it can be easily adapted for a range of musical modes and styles.

Tracing the oud’s development back into antiquity is difficult. Archaeologists and musicologists point to various pieces of the historical record that attest to something like the oud–a stringed instrument–perhaps stretching back to the ancient Near East. However, it is difficult to say if those instruments really can be considered ouds as we understand them today. The first clearly oud-like instrument arguably appears in the historical record during the Sassanian period. 14th century historians Abū al-Fidā, or Abulfedae, and Abū al-Walīd ibn Shihnāh place it in the reign of the Sassanid King Shāpūr I (241–72).

In the 8th century, the Abbasid court musician Mansour Zalzal made various changes to the design of the instrument and contributed greatly to its musicological development. It is generally from here that oud aficionados comfortably start the story of the instrument.

Throughout the centuries of its existence, the oud transcended borders and became a prominent court and folk instrument from the Maghreb to the territory of modern Iran, spreading by the 20th century to traditional ensembles in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and even Southeast Asia, to countries like Indonesia where it is called the gambus. Some historians argue the oud served as a predecessor to the European lute and guitar.

To understand how the oud has developed in different countries, one of the most interesting facts to keep in mind is that the history of the instrument is not continuous in each context. Rather than speaking of the development of the “oud tradition,” it should be understood that there are a wide variety of oud traditions, many of which are based on revived uses of the instrument or invented traditions. Instead of exoticizing the oud as an ancient instrument, passed down from the generations, it makes sense to see the oud’s history as a series of musical fits and starts with many golden eras throughout.

The clearest illustration of this aspect of the oud’s history is in Iran, where the oud disappeared entirely as a court instrument – although it continued to exist in folk contexts – sometime between the Safavid and Qajar period, only to be revived in the 20th century. Certain contemporary oud players and luthiers refer to the oud as a barbat, drawing on the previous Persian name of the oud.

Migration also played an important hand in the oud’s spread and use, including in moments of catastrophe. In Greece, the instrument is associated with refugees from Asia Minor who popularized their repertoire on the instrument. In the Armenian context, while the oud was used in Armenian communities of Western Armenia (particularly urban communities), the Armenians of the Caucasus and the Republic of Armenia were likely introduced to the oud only after the Armenian genocide. This mix includes a recording from the Cypriot Armenian, Soghomon Altunian and his student Stepan Mamoian, who is credited with bringing the oud to Eastern Armenia. In effect, this moment in history produced or at least restarted an oud tradition in a location that previously may not have seen use of the instrument prior.

As this mix shows, musicians of the world continue to write the story of the oud. Whether it be through new fusions of genres, electric ouds, or simply perfecting classic repertoires, the development of the oud continues–we just have to make sure that we are listening.

Tracklist and Track Origin Info:

- Munir Bashir and Omar Bashir – Dabke: Iraqi Maqam, interpolating other melodies and influences including Kurdish melodies

- Moza Khamis – Athabtni Ya Asmar: Mixed Omani and Bahraini Style

- Ali Azad Doulabi – Sekhane Zolm: Southern Iranian Style Oud

- Excerpt from Live Performance; Saghinameh Dar Adab Parsi – Mansour Nariman (Oud) And M.R. Shajarian (Vocals): Oud Performing Iranian Dastgah Repertoire

- Udi Hrant – Huzzam Sarki Medley (Gezidigm Dikenli Ask Yollarinda and Hoknadz Durmadz): Armenian oud player in Ottoman Art Music Style performing a medley in Turkish and Armenian

- Roza Eseknazi accompanied by oud player Agapios Tomboulis (Hagop Stambulyan): Greek Rembetika/Smyrneika style

- Richard Hagopian – Husseyni Saz Semaisi (composition by Kemani Tayos Ekserciyan): Armenian oud player performing in Ottoman Art Music Style

Cover Image: The Yasser Alwan Collection, Akkasah: Center for Photography, ref1142.