The following is a guest post by Munazza Ebtikar, a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Oxford and a native of Balkh and Panjshir, Afghanistan. She tweets at @mebtikar.

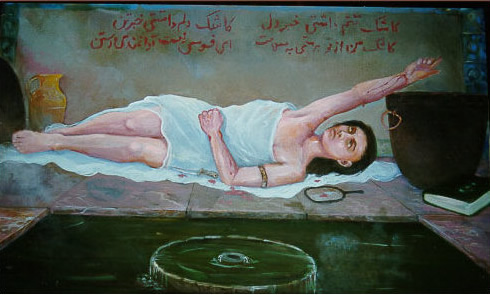

سر انگشت در خون میزد آن ماه ز خون خود همه دیوار بنوشت

The moon-faced beauty struck blood with her fingertip

With her blood she covered the walls

بدرد دل بسی اشعار بنوشت چو در گرمابه دیواری نماندش

Many poems stemmed from her agonized heart

When no walls remained in the hamam

ز خون هم نیز بسیاری نماندش همه دیوار چون پر کرد ز اشعار

So, too, a few drops of blood remained

As she covered the walls with poetry

فرو افتاد چون یک پاره دیوار میان خون و عشق و آتش و اشک

She collapsed like a fragment of a wall

Amid blood, love, fire and tears

بر آمد جان شیرینش بصد رشک

Her sweet soul swiftly left her body with a hundred desires.

-Sufi poet Farid al-Din Attar in the Ilahi-Nama

“Rabia slits her wrists so she can write her final love poem on the walls of the hamam with her blood,” narrates my aunt, sitting cross-legged on a red Afghan rug, designed with repeated octagonal patterns. We are in her daughter Rahima’s house in Khair Khana, a neighborhood in the north of Kabul. The sun rays cast a halo on her braided white-peppered brown hair. She balances a glass filled with steaming green tea in one hand, while the other raises a pink fly swatter in the air. Her eyes search for the buzzing menace and shift to mine, anticipating a reaction. I give her a knowing look of acknowledgment at the story’s tragic end. Her eyes search around the room as she explains the final act in a raised voice. “It must be understood: Rabia did not kill herself for Baktash.” She looked at me again. “She found love in God through Baktash; her heart was too pure in the face of injustice, you see.”

My aunt is narrating the tragic love story of Rabia Balkhi, a medieval poetess from Balkh, located in present-day northern Afghanistan. Rabia is one of the most venerated female figures in the Afghan imaginary. She is credited with having been among the first practitioners of New Persian or Parsi-ye Dari (tr. Persian of the Court). The language flourished in the 10th century after two centuries during which the Islamic conquest transformed the region’s cultural and linguistic composition, infusing Middle Persian (Pahlavi) with new vocabulary and a new script. Rabia was a poet princess in the Balkh court where her father served as Emir. She fell in love with her brother’s Turkish slave, Baktash, and would write poetry to him. Because of her brother’s jealousy and wickedness, he cast Rabia into the hamam and Baktash into a well. In the hamam, Rabia slit her wrists and with her blood she wrote her last love poems until her death.

“You see they don’t tell you, her love for Baktash is not like what you see in these TV shows.” We both glance at the Persian-dubbed Turkish show playing on the TV screen. The picture is blurry, but one can make out a man gazing into the hazel eyes of a beautiful Turkish woman. “She was a pure woman. Her burial site is a sacred shrine. I’ve been there,” my aunt says, nodding her head. My aunt narrates Rabia’s love story by adding her own emphasis on what she finds significant, providing her own interpretation of the story. For my aunt, Baktash was the means by which Rabia could reach the divine. It is common to hear Afghans tell and retell her love story with different emphases, reflecting on the world around them to make sense of themselves and their lives in a specific time and place. Rabia is depicted as a feminist icon who spoke truth to power, a martyr for sacred love, or even a victim of honor within a patriarchal order.

Today, Afghans name their daughters and institutions – from schools to hospitals – after her. Monuments were built in her honor and her story became a part of Afghanistan’s national culture through theater performances and film productions such as the historic epic Rabia Balkhi (1974). More than a thousand years after her death, Rabia continues to figure strongly in the Afghan cultural imaginary.

Although Rabia remains prominent in Afghan popular memory, her life and poetry have not been subject to much scholarly inquiry. In fact, there are scant references and illustrations of her life in literature on Persian poetry in most languages, even in Persian. Scouring through bookshops and libraries in Kabul in 2019, I was able to find only a few works on Rabia. There were some illustrations of her love story in some books and some collections of excerpts of her poetry or, perhaps, poetry attributed to her. How then, do we know about Rabia’s poetry and love story? Why does the afterlife of her love story remain prominent in the Afghan oral tradition? And what do the differing accounts of her love story tell us about the ways in which Afghans imagine themselves?

Although no divan of Rabia’s work exists, Rabia’s story and her poetic verses appear prominently in the narrations of influential male Persian poets and biographical dictionaries (tazkirahs). The earliest biographical work of Persian poets, titled Lubab al-albab (tr. The Essence of Essences) written by Muhammad ‘Awfi (1171-1242 CE) in 1220, briefly mentions Rabia, her skill in Persian poetry and her intellect under the title Rabia bint Ka‘b al-Quzdari. The longest narration of Rabia’s life and poetry is in the lyrical poem of the Ilahi-Nama (tr. Book of the Divine) by the Sufi poet and hagiographer, Farid al-Din Attar (1145-1221 CE).

One of the mystical stories in the Ilahi-Nama is of the life and poetry of Rabia titled Hikayate Amir-e Balkh wa āsheq shudan-e dukhtar-e ō (tr. the story of the Emir of Balkh and his daughter falling in love). As the longest narration of her story and poetry, Attar narrates her story and poetry as a mystic, a common trend among Sufi poets after her time. Her love for Baktash, her brothers’ Turkish slave, is depicted as sacred and divine love, as it is through seeing him that she starts writing her love poetry and only through him that she experiences this love for the divine.

Attar claims that it was the Persian Sufi poet Abu Sa‘id Abul Khayr (967-1049 CE) who had informed him that Rabia became a mystic and that her poetry was for God. This story of love and sacrifice has parallels to that of Rabi‘a al-Adawiyya (714-801 CE) from Basra, one of the most prominent female saintly figures in Islamic history, renowned for her unwavering devotion to God. About 270 years after this narration, Nur al-Din Abd al-Rahman Jami (1414-1492 CE), the 15th century Persian Sufi writer and poet, mentions Rabia in the hagiography titled Nafahat al-Uns (tr. Breezes of Intimacy), mentions Rabia among thirty-three other female saints under the title Dukhtar-e Ka’b, Rahmat-ullah alayh (tr. The Daughter of Ka’b, May God Have Mercy on Her). In this passage, Jami also references Abu Sa’id Abul Khayr’s story, writing that the daughter of Ka’b was in love with the slave but her love was not for him. Building on the same tradition as Attar, he writes that when Baktash saw Rabia close to him, he laid a hand on her sleeve. In response, she scorned him and said, “Is it not enough for you to understand that this love is for God? Have I given you the occasion to enjoy me?”

From these textual accounts, we can infer that Rabia lived during the Samanid Empire, which stretched from Transoxiana to Khorasan in the 9th and 10th centuries. At the time, Balkh served as one of the empire’s main cultural centers and as the epicenter of Islamic scholarship and mysticism. It was home to great poets and Sufi masters, gaining epithets such as umm al-bilad (tr. the mother of cities) or qubbat al-Islam (tr. the dome of Islam). Rabia was the daughter of Ka‘b, a local Emir, and of Arab lineage. As an outcome of the Islamic expansion eastward, Balkh had become an important center of Arab settlement in the 8th century. As the daughter of an Emir, Rabia occupied an elite position as a member of the nobility and was educated and wrote poetry.

Unlike male poets, such as her contemporary Abu ‘Abd Allah Ja‘far ibn Muhammad Rudaki, who served as poet laureates in the court and were compensated for their literary services, female poets wrote more for individual desire. Rabia wrote in both Persian and Arabic. Her poetry has served a crucial and decisive role in the revival of Persian poetry as we know it today: it alludes to pre-Islamic kings and religions, and uses tropes and metaphors which recur in later Persian poetry. It is for this reason that Rabia remains a central figure in the making of the Persian literary tradition. Born three centuries before Jalal ad-Din Mohammad Balkhi (commonly known as Rumi), Rabia was a major contributor to the foundation of the Persianate literary canon.

What we know of Rabia’s poetry and life in textual accounts has been passed down by Sufi chains of transmission, all of which emphasize her sainthood. In circumstances where oral transmission is broken or a divān is lost, tazkirahs become the “sole repositories of memory about some individuals and fragments of their verses.” Tazkirahs, according to Zuzanna Olszewska, “offer useful insights into the changing ways in which public narratives of distinction, or the distinctiveness of literary personalities, could be constructed and the types of people whose distinctiveness could be claimed.” Perhaps it is this emphasis on her sainthood that may explain why her mausoleum today, located in Nawbahar in Balkh, is one of the most frequently visited sites by pilgrims, tourists, and locals alike. Nawbahar itself is a famous pilgrimage site comprising tombs of pious men and women. This site holds a sanctity that predates Islam as it was also a spiritual site for Buddhism and Zoroastrianism.

Afghans tell and retell Rabia’s story and poetry through diverse avenues, and in diverse social and political contexts. Rabia is memorialized and immortalized by her narrators. Olszewska describes composing and writing poetry in Afghanistan to be “the most highly prized and widely practiced art form among Afghans of all walks of life, both literate and illiterate.” In one sense, Rabia’s popularity in Afghanistan is like Ferdowsi’s in Iran, which, as Aria Fani writes, was “the product of intellectual and architectural labor sponsored by the state.”

Afghan nationalists in the 20th century worked to create and promote a distinctive “Afghan” national and historical identity, privileging their own canon of writers whose birth fell within the borders of the nation-state. This explains why one of the first government-sponsored Afghan films was on Rabia and why many all-women institutions, such as schools and hospitals, were named after her. But, in another sense, Rabia’s love story with Baktash resembles the great tragic love stories of Persian literature – such as Leili and Majnun or Khosrow and Shirin – allowing it to be easily narrated and passed down from one generation to the next.

My aunt in Khair Khana retold Rabia’s story to make her own point about the power of love and God. For my aunt, Rabia’s love contrasted with the modern-day love portrayed in the Turkish serial drama airing on the small TV set in front of her. Yet, hers is only one version of Rabia’s love and life represented in the Afghan popular imaginary. In her exhibition of notable women in Afghanistan and the region “Abarzanan” (tr. Superwoman), held in Kabul in 2018, Afghan artist and photographer Rada Akbar displayed a red dress to represent Rabia. She described Rabia as “a symbol of defiance against patriarchy and a continued harsh reminder of the price we’ve [Afghan women] been forced to pay for freedom of speech and love.”

This has parallels to an article written on Rabia published in the popular magazine, Zhvandun, more than 40 years prior in 1974. The first line of this article reads, “the story of Rabia is the story of a cry in the strangled throat of the women in our society in her time and other times that have passed.” Although 40 years apart, both interpretations reflect on the dire place of Afghan women within a patriarchal society – as well as how Afghan women have claimed Rabia’s legacy as a means of resistance.

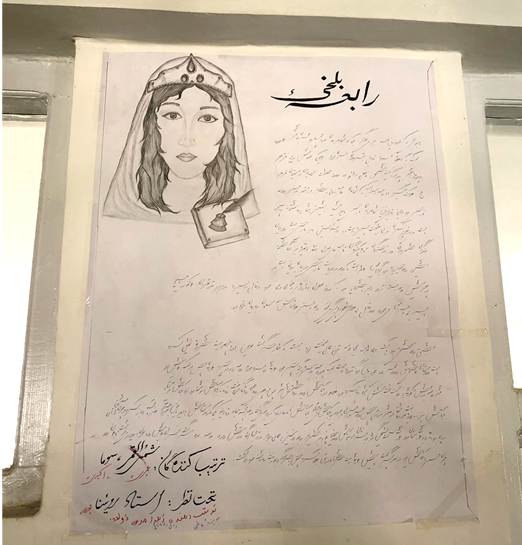

Julie Billaud, in her ethnography titled Kabul Carnival: Gender Politics in Postwar Afghanistan, notes the popularity of Rabia among female students at Kabul University. They admired Rabia’s heroism in choosing self-sacrifice and death to defend greater ideals. Self-sacrifice, according to Billaud, is part of these Afghan women’s broad repertoire of emotional performance. Comparingly, when I visited all-girls schools in Kabul and Panjshir in 2019, descriptions or drawings of Rabia adorning hallway walls (See Figure 6) was a common sight. Rabia’s legacy inspires young women to defy and transcend the unjust limitations placed – and worldviews held – within their society. As such, Rabia’s defiance and bravery to reach her earthly love, Baktash, the divine, or both, in her life and her poetry remain central in the Afghan cultural imagination one thousand years after her death.

Although Rabia’s story takes many forms, her story which I heard told and retold in Afghanistan has a common version, and it goes as such.

In the sacred land of Balkh with its one thousand mosques, Rabia, the daughter of the Emir of Balkh, is born. She is bathed in rose water, adorned in silk, and placed in a carriage made of gold. The day of her birth is celebrated by the people of Balkh, and they rejoice as they pray and read poetry on this auspicious day.

Rabia is raised in the palace where she is taught arts and literature, hunting and archery, until she reaches the age of wisdom. She was enchanting, both in her beauty and her words. She moved and spoke with an eloquence that left her with many admirers. When Rabia recited her poetry, it would bewilder the poets and literati of her time. She captured not only the hearts of her mother and father, but the people of Balkh themselves nicknamed her Zain al-Arab (the beauty of the Arabs, or the most beautiful one of the Arabs), Iqbal (the auspicious), and Tela-ye Ka‘b (the gold of Ka‘b). Her youth and charm would illuminate the eyes of her aging father.

One day, a famous astrologer of Balkh named Atrosh tells her that although she is an irradiating star and will set the world aflame with her passion, she may fall into bad omen.

Rabia’s mother passes away and this shatters her delicate being. The women of her court took Rabia to places of worship so that her soul was soothed by the sermons and verses of the great scholars and men of wisdom from Balkh.

Meanwhile, her brother Haris was jealous and envious of Rabia’s skill, eloquence, and the admiration she received from her father and the people of Balkh. When their father is on his deathbed, he calls them both to him. He tells Haris that he will be his successor and advises him to be just and generous with all of God’s creations, and to ensure that he will look after Rabia.

∙∙∙

One day as Rabia stands on her balcony overlooking a garden, she catches sight of a beautiful man serving wine to Haris. Baktash, Haris’s Turkish slave and a guard of the treasury, captures Rabia’s heart. This moment marks the beginning of Rabia’s love story and poetry, and her tragic fate.

Rabia would compose love letters to Baktash in verse, longing for him. These would be delivered by her loyal court maiden and friend, Ra‘na. Her love for Baktash was an affliction that no doctor of Balkh was able to cure.

Rabia writes:

الا ای غائب حاضر کجائی

Oh the absent and present one where are you

به پیش من نهٔ آخر کجائی

If you are not with me then where are you

دو چشمم روشنائی از تو دارد

My eyes are illuminated by you

دلم نیز آشنائی از تو دارد

My heart is acquainted by you

بیا و چشم و دل را میهمان کن

Come and invite my eyes and soul

وگرنه تیغ گیر وقصد جان کن

Otherwise take a sword and end my life

Baktash, in response, says:

ندارم دیدهٔ روی تودیدن

I don’t have the sight to see you

ندارم صبر بی تو آرمیدن

I don’t have patience and rest without you

مرا اکنون چه باید کرد بی تو

What am I going to do with you now

که نتوان برد چندین درد بی تو

How can I carry this pain without you

چو زلف تو دریده پردهام من

Your hair has pierced my veil

که بر روی تو عشق آوردهام من

With your face I have fallen in love

ازان زلف توام زیر و زبر کرد

From your hair I have become under and over

که با زلف تو عمرم سر به سر کرد

Because from your hair my life has been destroyed

∙∙∙

During this time, Asher al-din, the ruler of Kandahar, sought to attack Balkh and subject it to his rule. Haris, who had claimed his throne, was fearful and prepared to stand in opposition. With the consultation of his advisors, he knew that without the help of Baktash, he was unable to defeat his enemy.

Haris tells Baktash that if he kills Asher al-din, he will reward him with what he pleases. In the battlefield Baktash was victorious but at a dear price. As he nearly lost his life, a soldier with a covered face came galloping into the battlefield to save him and win the war. This soldier was none other than Rabia.

∙∙∙

Balkh was the epicenter of literary events, but it was unmatched by Bukhara. Amir Nasr, the king of the Samanids, was a lover of poetry and organized grand literary events in Bukhara, the home of the great poet, Rudaki. One day, Haris was invited, together with the newly defeated Asher al-din of Kandahar, the ruler of Herat, and other notables, to witness Rudaki recite his poetry.

When Rudaki recited his poetry, he dazzled his audience. One of his poems was Rabia’s, whom he would join in the Balkh court. After he recites her poem, he attributes it to her and says that although Rabia is a sacred woman, she fell in metaphorical love with her slave Baktash, the inspiration behind this poem. When Haris hears this, he coils like an injured snake. The event comes to an end and Haris takes towards Balkh, thirsty for the blood of Rabia and Baktash who had brought shame to his name.

Upon his arrival to Balkh, Haris orders that Rabia be thrown in the hamam and Baktash in a well. In the hamam, she slashed her wrists, and writes the last few lines of poetry for Baktash with her blood on its walls. After days of being in the well, Baktash is saved with the help of Ra‘na. He first takes Haris’s head and goes to the hamam, only to find Rabia’s beautiful lifeless body on the ground covered with her blood and the walls of the hamam adorned with her last love poems for Baktash. He falls to the ground and takes his life next to his beloved.

One of the poems that are on the wall reads:

کاشک تنم يافتي خبر دل

I wish my body was aware of my heart

کاشک دلم داشتی خبر تن

I wish my heart was aware of my body

کاشک من از تو برستی به سلامت

I wish I could escape from you in peace

آی فسوسا کجا توانم رستن

Where can I go regretfully

References

Azad, Arezou. Sacred Landscape in Medieval Afghanistan: Revisiting the Faḍa’il-i Balkh. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Billaud, Julie. Kabul Carnival: Gender Politics in Postwar Afghanistan. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Davis, Dick. The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women. Penguin Books, 2019.

Olszewska, Zuzanna. “‘A Desolate Voice’: Poetry and Identity among Young Afghan Refugees in Iran,1.” Iranian Studies, vol. 40, no. 2, 2007, pp. 203–224.

Olszewska, Zuzanna. “Claiming an Individual Name: Revisiting the Personhood Debate with Afghan Poets in Iran.” The Scandal of Continuity in Middle East Anthropology: Form, Duration, Difference, edited by Judith Scheele and Andrew Shryock, Indiana University Press, 2019.

1 comment

Rabia Balkhi’s blood is still seeking freedom and the search for her killer from behind the gates of history. A murderer of his own blood and his brother. She was killed for love and was imprisoned in the corner of the house. She had a passion for freedom and died in the bathroom. This is the story of the girls of my land who are still imprisoned with the same regret and their blood is flowing behind closed doors and suffocating veils.