This article originally appeared in the 2015 edition of Tirgan Magazine, as part of its segment on “artifacts”. This is the official magazine of the biannual Tirgan festival based in Toronto. This festival celebrates Iranian art and culture from within Iran and across the global Iranian diaspora, and is the largest of its kind outside of Iran. Other entries from Tirgan Magazine are available here.

“Artifacts” are cultural condensation. They are the objects that put into relief a certain way of life, identity, historical period, social entanglement, etc. Just like “keywords”, they offer a great way to glimpse a bigger picture.

Anyone who has had the misfortune of sitting in Tehran traffic has witnessed a distinctive sea of white vehicles, horns blaring and congesting the highway. This amorphous mass of metal and rubber is predominantly composed of the Paykan—Iran’s most iconic car—and it has dominated the Iranian streets since the late 60s. With nearly 2.2 million units sold throughout its production run, it accounted for 40% of all Iranian automobiles at the time of its discontinuation in 2005. The Paykan, like many of its drivers, has survived the tumult of revolution, war, reconstruction, and economic crises. The resilience of the Paykan mirrors that of 20th and 21st Century Iran, which can explain why it still endures not only as functional car, but also as a symbol of collective experiences and an object of nostalgia.

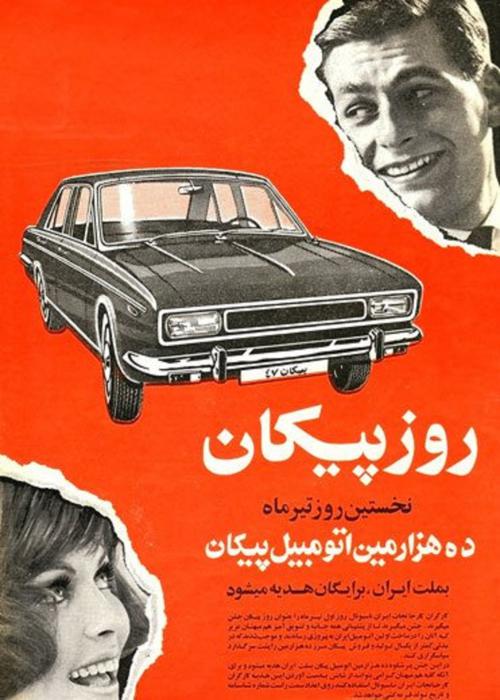

Throughout its history, the symbolic significance of this car has changed dramatically depending on social, political, and economic circumstances. The Paykan (which means “arrow” in Persian) has its beginnings in 1962, during a period of massive socio-economic transformations in Iran. Taking advantage of the Iranian government issuing of loans and tax benefits to promote new industries, brothers Ahmad and Mahmoud Khayami founded Iran National, and acquired the rights to produce a version of the British-owned Rootes Group Arrow.

The economic incentives that encouraged the formation of the company corresponded with the “White Revolution,” a series of socio-economic reforms proposed by the Pahlavi government. Throughout the 60s and early 70s, a language of “modernization” circulated in public discourse, and many individuals in the government believed that urban industrialization—combined with rural land reform, political restructuring, and new educational programs—would end many of Iran’s “backward” institutions.

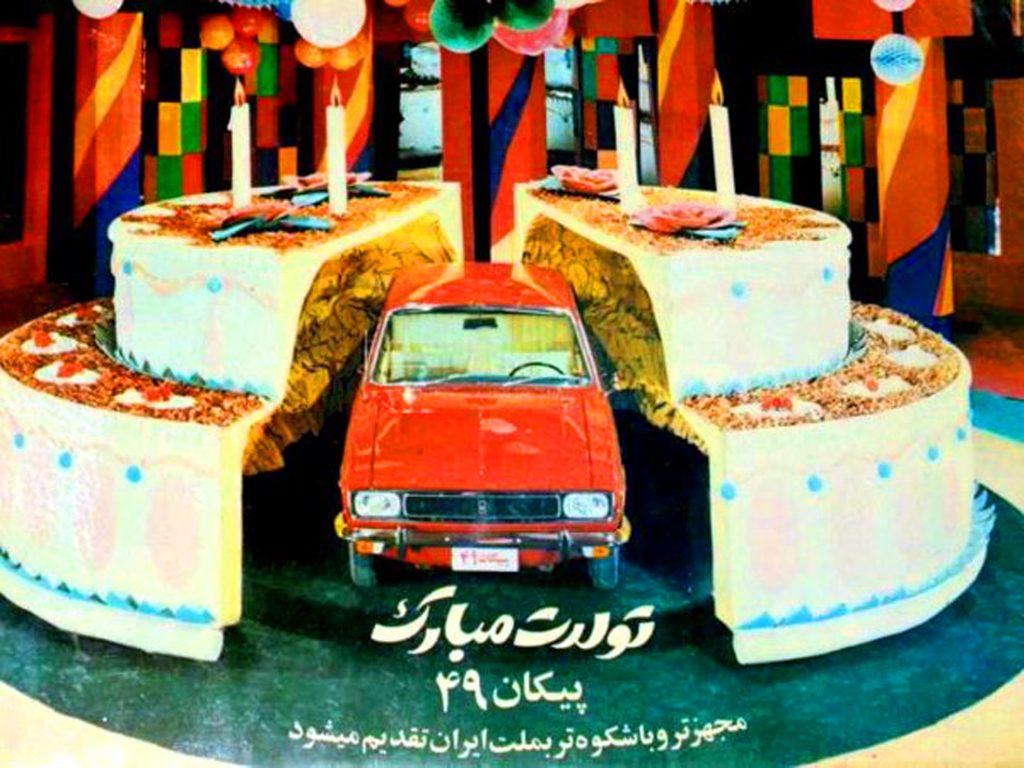

As Iran’s first domestically manufactured car, the Paykan played a significant role in the formation of a new Iranian middle class, as defined by the Pahlavi government. The vehicle was introduced around the time of massive economic growth in the country, and the foreign origins and the “British cool” style of the Paykan were attractive to the consumerist mentality of the emergent middle class. By the early 1970s, Iran national had increased production of the Paykan and manufacturing numerous models, such as a station wagon, pickup, and automatic versions.

During the 1978-1979 Revolution, the Paykan served as a tool for protest, bringing many protestors to demonstrations all over Iran, with their horns signaling celebrations in the streets with the flight of the Shah. The Khayami brothers also left the country and Iran National was nationalized and renamed Iran Khodro. The revolutionary regime strove to distance the Paykan from its Pahlavi-era image and stripped the car of many of its luxury features—such as its interior wood paneling, chrome fenders, and radio. These downgrades performed a symbolic function; they mirrored the socio-political ideals of the early Islamic Republic, when conspicuous consumption was considered inimical to the austerity of revolutionary Islam.

The Paykan continued to be produced during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88), but a wartime economy meant that they were of inferior and inconsistent quality. To improve the car’s off-the-line performance, owners often visited specialized auto shops that would replace the Paykan’s standard parts with spare foreign imports. The Paykan was no longer perceived as a luxury vehicle; now it was as a battle-hardened ride that was customizable and easily repaired.

Perceptions of Iran’s national car seemed to indicate broader socio-economic circumstances that affected the country as a whole. Just as the Iranians were beginning to recover from the war, international sanctions and embargoes placed upon Iran once again added to the struggles of the people. The Paykan lost it status as a symbol of social mobility and their drivers often resorted to informal work like mosaferkeshi (the practice of picking up multiple passengers for a small fare) in order to supplement their income.

By the 2000s, the Paykan was being outperformed by newer automobiles on the market. With no airbags, automatic braking systems, and failing to meet international environmental requirements, many Iranians were relieved to see the end to the out-dated gas-guzzler and the transition to more modern-looking models, such as Iran Khodro’s Samad and domestically produced French vehicles. Despite the car’s spartan qualities, however, the Paykan has remained significant in Iranian society due to the fact that it was at the center of personal and collective memories.

Whether driven for work, family use, or taxiing, the Paykan was a means of social exchange. For many Iranians, the Paykan was their first car they were able to purchase, allowing them to navigate the public sphere in a closed, semi-private environment. From family vacations to political discussions with strangers in the back of a taxi, almost all urban Iranians can recall some memories that occurred inside a Paykan. Through the shared experience of travel, the Paykan helped facilitate a sense of national coherency similar to other transportation and communication technologies, like the national railway or the radio.

Considering the Paykan’s role in the formation of human lives, it is no surprise that the car has a privileged position in Iranian cultural memory. Such respect for the Paykan was demonstrated during the funerary-like ceremony celebrating the end of the car’s illustrious career in May of 2005. At the event, government officials gave speeches about the significance of the car, and the last Paykan ever produced was covered in a black cloth reading “Farewell, Paykan” and formally sent off to a museum where it would be revered as a socio-cultural artifact.

As the number of Paykans on the street has started to dwindle over the last ten years, the car has been increasingly featured in cultural spaces and products in and outside of Iran. Recently, two exhibitions at the Dastan Gallery and the AUN Gallery in Iran have focused on the Paykan. In music, bands such as Ajam and Kiosk have featured the car in their music videos and album covers, respectfully. The Paykan has even made its way into digital media, as a new generation of admirers has created online spaces (such as Shahin Armin’s Paykan Hunter blog) to collect any information, documents, and photographs about Iran’s most famous car. In the realm of cultural production, the Paykan will continue to represent something uniquely Iranian.