Joseph Bohigian is a composer and performer whose cross-cultural experience as an Armenian-American is a defining message in his music. His work explores the expression of exile, cultural reunification, and identity maintenance in diaspora. Featured image taken by Shumaila Hemani.

What does it mean to write music of diaspora? How can music be both of a place and not of it? These are questions I have asked myself as I’ve endeavored to write music from an Armenian diaspora perspective. Given our history of displacement and genocide, I often find myself symbolically recreating a world that no longer exists through sound. Considering how my own diasporic background influences my compositions, I am fascinated by the ways composers from other diaspora communities likewise use music to understand their relationship with Home, whether that Home is one in which they were born, or one to which they have never been.

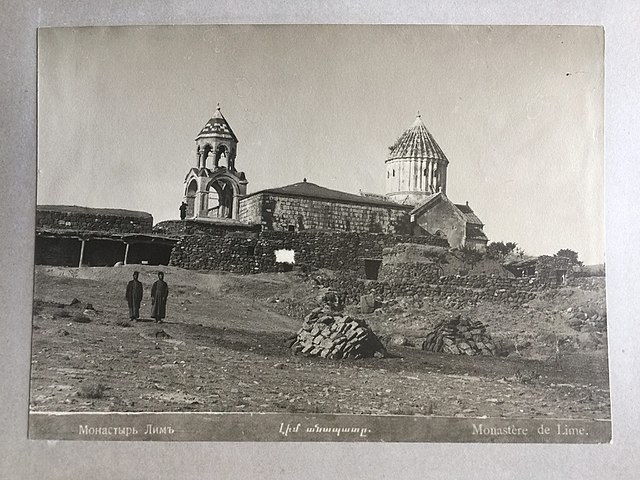

This mixtape explores the ways four contemporary composers with roots in the lands between Anatolia and South Asia have turned to music to examine their relationship with Home from diaspora. Their approaches to expressing Home from afar vary from the use of texts to the sounds of Home themselves, yet they are tied together by a desire to more deeply understand a place with a perspective gained through distance. Mary Kouyoumdjian explores the psychology of the painter Arshile Gorky as he is symbolically returned to the home he lost during the Armenian Genocide. Shumaila Hemani guides listeners through the Shrine of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai in Pakistan to convey sonic expressions of Islamic beliefs as she experiences them. Niloufar Nourbakhsh sets a poem by Forugh Farrokhzad that reflects contemporary issues of justice in Iran. Finally, Yiğit Kolat investigates the suppression of cultural memory in Turkey through the deconstruction of a Kurdish folk song recording.

A connection to Home is a vital presence in the work of Armenian-American composer and documentarian Mary Kouyoumdjian. Like most diasporic Armenians, displacement is a central part of Kouyoumdjian’s family history. Her grandparents and great-grandparents fled the Armenian Genocide and settled in Beirut, only to again be displaced during the Lebanese Civil War. The sounds of Home played a prominent role in Kouyoumdjian’s upbringing. Growing up, her father played records of Armenian folk music and 1960s and 70s Lebanese pop at the dinner table. As a teenager, she was not partial to this music, but its sounds which evoke a connection to her family’s history grew to be cherished to her and became integrated into her compositional voice.

The centrality of exile in the Armenian collective consciousness has been a source of artistic inspiration for many of Kouyoumdjian’s works. Her piece “Where Once” from Gorky is an “imagined monologue” for the influential Armenian-American Abstract Expressionist painter Arshile Gorky as he paints his mother’s likeness in The Artist and His Mother. Gorky was a child at the start of the genocide in 1915, when he fled his hometown on Lake Van with his mother and sister. In the painting, which he began in 1926, Gorky recreates a 1912 photograph with his mother, who died four years after their escape, reimagining an Armenia which no longer existed.

This phenomenon of looking back toward a lost homeland is also present in “Where Once,” wherein Kouyoumdjian probes Gorky’s psychological state as he symbolically returns himself and his mother to the familiar setting of Home. The text, by librettist Royce Vavrek, was inspired by letters supposedly written by Gorky, although they were in fact fabricated by his cousin after Gorky’s death. In the music, Kouyoumdjian leans into the horror of Gorky’s childhood experiences, pleading to be taken back to Van and returned to the water.

Shumaila Hemani, Ph.D. is an Alberta-based acousmatic composer, Sufi singer-songwriter, and ethnomusicologist whose musical practice is rooted in the singing of traditional Sufi Islamic poetry. Describing her practice, she states, “[w]hat listening offers us is the most visceral, immediate, and intimate doorway into realizing and practicing our humanity during any global crisis.” Built on the idea of “sonic photographs,” Hemani’s Forgotten Ways of Thinking, a pioneering soundscape piece from Pakistan, communicates the sonic expressions of Islamic beliefs and reflections on her subjectivity as a female ethnographer observing women’s possessed voices at the margins of a male-centered Sufi performance. Hemani created the piece on a 2009 trip to Bhitshah, Pakistan to research the tradition of the Shah jo Raag, the sung poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, that became the focus of her 2019 dissertation at the University of Alberta.

Throughout the work, the composer guides listeners through her experience at the Shrine of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai in a form reminiscent of the soundwalks of Canadian composers such as R. Murray Schafer and Hildegard Westerkamp (her current mentor) which emphasize an aural focus on the natural and built environment as one traverses it. Forgotten Ways of Thinking is also a personal reflection on Hemani’s religious upbringing in her hometown of Karachi rooted in the Shi’ite Ismaili world of singing hymns (ginans) and belief in Imam Ali, the first spiritual leader who connects all Shi’ite denominations. Hemani’s understanding of the sounds of Pakistan was not only informed by her study of Canadian soundscape composition, but also her immersion in sounds from other Muslim contexts through her educational travels in Syria, Egypt, Spain, Tajikistan, and Muslim diaspora communities in the UK while pursuing a graduate certificate in Islamic Studies & Humanities. Though she had become secular since her undergraduate study in Lahore, Hemani’s inspired engagement with Sufi sounds of Pakistan led her to travel to Bhitshah to learn the Shah jo Raag tradition from the hereditary community of the Raagi faqirs who have been passing on this tradition for about 300 years. Her trail-blazing work on the tradition of the Shah jo Raag is reflected in this composition which expresses the belief and practice of “spirit possession and exorcism” in Sindh and the ways in which women’s possession is expressed and conceived within a male setting.

Composer/pianist Niloufar Nourbakhsh was born in Iran and moved to the United States at 18 to attend university in Maryland. Nourbakhsh describes her history and identity as being ingrained in her work at a subconscious level. This manifests in both musical contexts, for example the influence of meditative repetition in the Sufi music she associates with her upbringing, and in her choice of thematic material as she watches events in Iran from afar. In The Window, she sets a poem by Forugh Farrokhzad the thematic content of which she ties to her feelings about Iran and a sense of helplessness in the face of being so far away from Home. As Nourbakhsh describes it, quoting Farrokhzad, when one’s trust is “hung from the feeble rope of justice,” the only option left is to “deliriously love.”

Yiğit Kolat’s Messenger of Sorrows is structured by two musical processes. The first is inspired by Alvin Lucier’s I Am Sitting in a Room, in which the sound of the composer’s voice is repeatedly played, recorded, and replayed, gradually revealing the resonant frequencies of the room. In Messenger of Sorrows, Kolat’s resonances come from a room being destroyed. Through a convolution process which digitally simulates the way sound behaves in a space, Kolat imagines the resonant properties of a room in a Kurdish house in Cizre as it is being struck by a rocket during a curfew imposed by the Turkish government in 2015. The convolution process is such that a recording of the Kurdish folk song “Dar Hejîrokê” sung by Aynur Doğan is repeatedly played and replayed within the context of Kolat’s imaginary impulse response derived from a recording of the rocket hitting the house. As the composer puts it, “it was as if the sorrowful inflections of this folk song were absorbed by the walls of the wrecked house, and the inflections were slowly being retrieved during the process.”

The second process is one of increasing illegibility in the score. At the beginning of the piece, the score is highly detailed and precise. As the piece progresses, details become blurred and by the end of the work, the score is totally illegible. As the score gradually loses its ability to communicate, the performers must increasingly rely on improvisation to interpret it. Kolat’s interest in this process is in the gray area between development in composition and spontaneous improvisation.

Excerpt from Kolat’s score for Messenger of Sorrows

According to Kolat, living outside of Turkey allowed him to step out of the paradigm in which Turkish composers are expected to incorporate the music of their homeland in their work and favoring Western trends is a sign of assimilation. He writes of this shift, “snatching a folk song from its natural habitat by stripping it from practically every aspect that constitutes its musical identity—timbre, tuning, musical timing, form, performance practice, and presentation—to present a specter of it in a Western setting, was the actual act of assimilation.” This realization revealed opportunities to interact with the musical idioms of his homeland without the need to place them in a foreign context. For Kolat, this approach demanded a focus on the historical and social context of the material. In Messenger of Sorrows, Kolat traces a history of suppression and distortion of cultural memory by drawing on the echoes of war, massacre, and genocide behind lyrics, stories, and fables such that they might speak to our present.“ In countries like Turkey,” he says, “such lyrics would also point to the future, given the endless recurrence of state violence against minorities and other targeted groups.” For Kolat, Turkey “is not only a geographical/cultural/historical entity but also a field of struggle” to which he aims to lead some attention with his music.

As this mix shows, though a variety of approaches from tapping into a culture’s collective memory to gaining a new perspective through distance, these composers effectively use sound to find Home.

Tracklist:

Mary Kouyoumdjian – “Where Once” from Gorky, libretto by Royce Vavrek, performed by loadbang

Shumaila Hemani – Forgotten Ways of Thinking

Niloufar Nourbakhsh – The Window, performed by Zhanna Alkhazova

Yiğit Kolat – Messenger of Sorrows, performed by Inverted Space Ensemble